Overview for publishing API docs

As you look for ways to provide value as a technical writer in a highly technical organization, you might find that you do less direct authoring of technical content and more editing/publishing. You might be guiding and directing the publishing of technical content that engineers mainly develop. For this reason, I have a lengthy focus on publishing in this course about documenting APIs.

- Why focus on publishing API docs?

- Using tools your SME authors want to use to collaborate

- 1. The HAT tooling doesn’t match developer workflows and environments

- 2. HATs won’t generate docs from source

- 3. API doc follows a specific structure and pattern not modeled in any HAT

- 4. Many APIs have interactive API consoles, allowing you to try out the calls

- 5. With APIs, the doc is the product’s interface, so it has to be attractive enough to sell the product.

- A new direction: Static site generators

- Video about publishing tools for API docs

Why focus on publishing API docs?

The first question about a focus on publishing API documentation might be, why? What makes publishing API documentation so different from publishing other kinds of documentation such that it would merit its own section? How and why does the approach with publishing API docs need to differ from the approach for publishing regular documentation?

With API documentation, you’re no longer in the realm of GUI (graphical user interface) documentation, usually intended for mainstream end users. A lot of the content for developers is complex and requires a background not just in programming, but in a specific programming language or framework.

As such, you may find that as a technical writer, you’re in over your head in complexity and as such, you’re reliant on engineers to write more of the content. You end up playing of a doc tooling and workflow role.

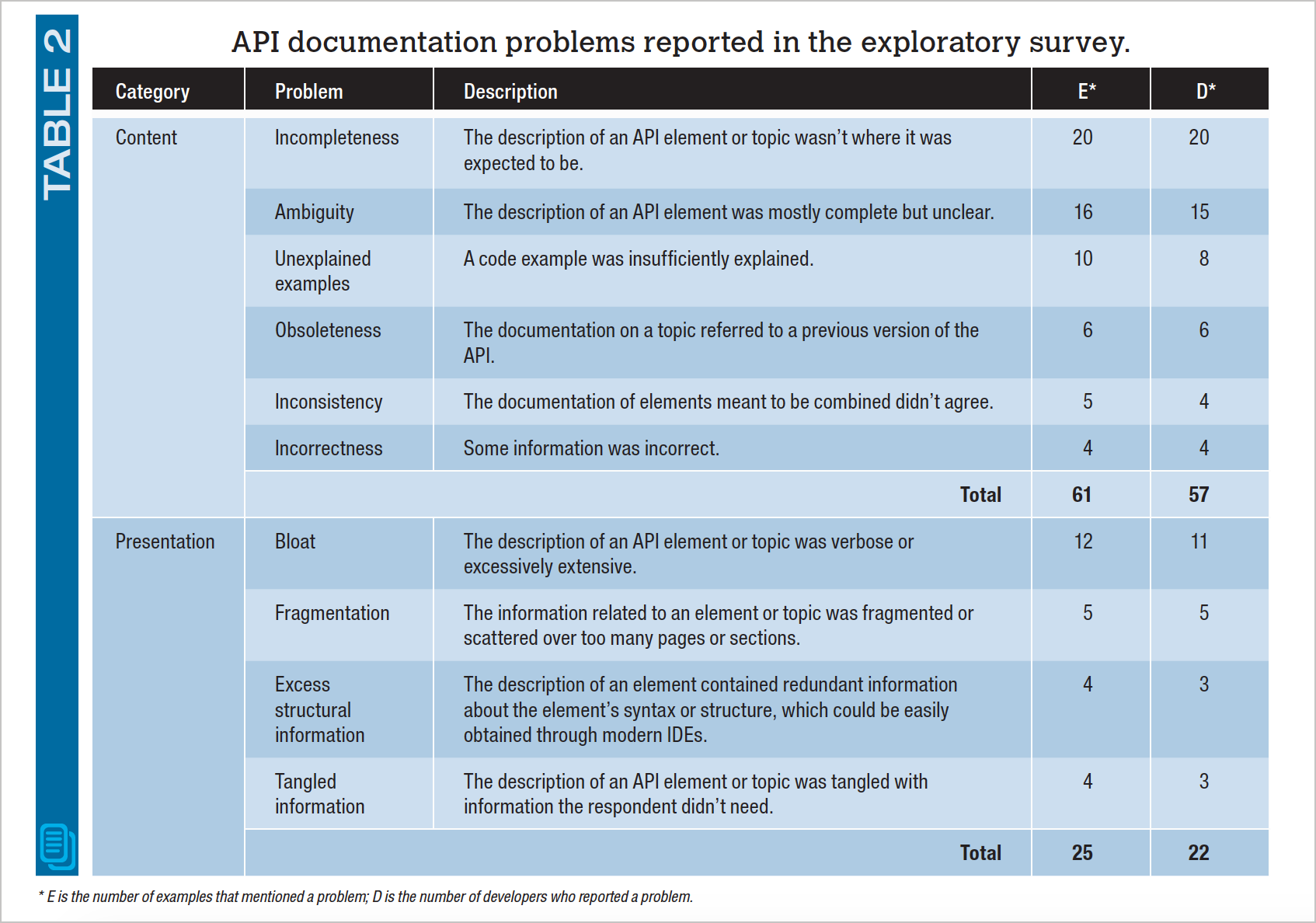

In How API Documentation Fails (published in IEEE Software), Martin Robillard and Gias Uddin surveyed developers to find out why API docs failed for them. They found that most of the shortcomings were related to content, whether it was incomplete, inaccurate, missing, ambiguous, fragmented, etc. They summarized their findings here:

The problem is that the very people who can fix this content are usually fully engaged in development work. Robillard and Uddin write,

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the biggest problems with API documentation were also the ones requiring the most technical expertise to solve. Completing, clarifying, and correcting documentation require deep, authoritative knowledge of the API’s implementation. This makes accomplishing these tasks difficult for non-developers or recent contributors to a project.

So, how can we improve API documentation if the only people who can accomplish this task are too busy to do it or are working on tasks that have been given a higher priority? One potential way forward is to develop recommendation systems that can reduce as much of the administrative overhead of documentation writing as possible, letting experts focus exclusively on the value-producing part of the task. As Barthélemy Dagenais and Martin Robillard discovered, a main challenge for evolving API documentation is identifying where a document needs to be updated.

For example, suppose you identify a high point of developer friction related to poor documentation. Fixing it might not just be a matter of converting the content into plain language or adding some details about missing parameters. The required fixes might involve explaining how the parameters interact in the code, how one value gets used by another and how they get mapped into variables that the code iterates through, etc. Maybe the only person who truly understands the crazy syntax users have to write is the lead developer.

But guess what? What lead developer is going to have time to figure out docs? He or she is usually heads-down deep in a complex programming scenario. So the very person who has the knowledge to decompile and excogitate the needed concepts in the documentation usually isn’t available to do so. But if the content is beyond the comprehension of generalists, at some point, these SMEs will need to devote some time to docs. In these scenarios, Robillard and Uddin say the best help would be to reduce the overhead of the documentation process.

As an editor/publisher, you can help the SME author by accurately identifying the point of confusion, the area of the doc that needs updating, and provide easy tools for the SME to make the updates. The engineers can’t be bothered to figure out static site generators or publishing workflows, PDFs, or other doc publishing tools. By playing a role as an editor/publisher, you can be a valuable contributor to the product team. This publishing role is why being a doc tools expert is particularly relevant in API documentation contexts.

Using tools your SME authors want to use to collaborate

If engineers and SMEs will be collaborating on some of the doc content, consider using engineering-centric tools rather than writing-centric tools. When I first transitioned to API documentation, I had my mind set on using DITA, and I converted a large portion of my content over to it.

However, as I started looking more at API documentation sites, primarily those listed on Programmableweb.com, which maintains the largest directory of web APIs, I didn’t find many DITA-based API doc sites. It turns out that almost none of the API doc sites listed on Programmable Web even use traditional tech comm authoring tools.

Despite many advances with single sourcing, content re-use, conditional filtering, and other features in help authoring tools and content management systems, almost no API documentation sites (at least those listed on Programmableweb.com) use them. Why is that? Why has the development community implicitly rejected tech comm tools and their many years of evolution?

Granted, there is the occasional HAT, as with Photobucket’s API, but they’re rare. And it’s even rarer to find an API doc site that structures the content in DITA.

The short answer is that in API documentation scenarios, more engineers are writing. The content is so technical, they’re the only ones who understand it. And when engineers write, they’ll naturally gravitate towards tools and workflows they’re familiar with.

Andrew Davis, a recruiter who specializes in API documentation jobs in the Bay area, told me that specializing in docs-as-code tools is 100% more advantageous than becoming adept with DITA or some other traditionally technical-writer-oriented tooling.

Davis knows the market, especially the Silicon Valley market, extremely well. Without hesitation, he urged me to pursue the static site generator route (instead of DITA). He said many small companies, especially startups, are looking for writers who can publish documentation that looks beautiful, like the many modern web outputs on Programmableweb.

His response, and my subsequent emphasis on static site generators, led me to understand why traditional help authoring tools aren’t used often in the API doc space. To make the case even stronger, let me dive into five main reasons why tech writers use docs-as-code tools in developer documentation spaces:

1. The HAT tooling doesn’t match developer workflows and environments

If devs are going to contribute to docs (or write docs entirely themselves), the tools need to fit their own processes and workflows. Their tooling is to treat doc as code, committing it to version control, building outputs from the server, etc. They want to package the documentation in with their other code, checking it into their repos, and automating it as part of their build process. If you’re hoping for developers to contribute to the documentation, it’s going to be hard to get buy-in if you’re using a HAT.

Additionally, almost no HAT runs on a Mac. Many developers and designers prefer Macs because they have a much better development platform (the command line is much friendlier and functional, for example). If you’re using a PC, you might struggle to install developer tools or to follow internal tutorials to get set up and test out content.

Even if you could get developers to use a HAT, you’d likely need to buy a license for each contributing developer. In contrast, docs-as-code tools are often open source and can, therefore, scale across the company without budgetary funding and approval.

2. HATs won’t generate docs from source

Ideally, engineers want to add annotations in their code and then generate the doc from those annotations. They’ve been doing this with Java and C++ code through Javadoc and Doxygen for the past 25+ years (for a comprehensive list of these tools, see Comparison of document generators in Wikipedia).

Even for REST APIs, there are tools/libraries that will auto-generate documentation from source code annotations (such as from Java to an OpenAPI spec through Swagger Codegen), but it’s not something that HATs can do. For more on auto-generating from source, see Auto-generating the OpenAPI file from code annotations.

3. API doc follows a specific structure and pattern not modeled in any HAT

Engineers often want to push the reference documentation for APIs into well-defined templates that accommodate sections such as endpoint parameters, sample requests, sample responses, and so forth. (I discuss these reference sections in Documenting API endpoints.)

If you have a lot of endpoints, you need a system for pushing the content into standard templates. Ideally, you should separate the various sections (description, parameters, responses, etc.) and then compile the information through your template when you build your site. Or you can use a specification such as OpenAPI to populate the information into a template. You can also incorporate custom scripts. However, you don’t often have these options in HATs, since you’re mostly limited to what workflows and templates are supported out of the box.

4. Many APIs have interactive API consoles, allowing you to try out the calls

You won’t find an interactive API console in a HAT. By interactive API console, I mean you enter your own API key and values and then run the call directly from the web pages in the documentation. (Flickr’s API explorer provides one such example of this interactivity, as does Swagger UI.) The response you see from this explorers is from your own data in the API.

5. With APIs, the doc is the product’s interface, so it has to be attractive enough to sell the product.

Most outputs from HATs look dated and old. They look like a relic of the pre-2000 Internet era. (For more on the dated display, see Tripane help and PDF files: past their prime? from Robert Desprez.)

For example, here’s a sample help output from Flare for the Photobucket API:

With API documentation, often the documentation is the product’s interface — there isn’t a separate product GUI (graphical user interface) that clients interact with. Because the product’s GUI is the documentation, it has to be sexy and attractive.

Most tripane help doesn’t make that cut. If the help looks old and frame-based, it doesn’t instill much confidence with developers evaluating it.

In Flare’s latest release, you can customize the display in pretty significant ways, so maybe it will help end the dated tripane output’s appearance. Even so, the effort and process of skinning a HAT’s output is usually drastically different from customizing the output from a static site generator. Web developers will be much more comfortable with the latter.

A new direction: Static site generators

Based on all of these factors, I decided to put DITA authoring on pause and try a new tool with my documentation: Jekyll. I’ve come to love using Jekyll, which allows you to work primarily in Markdown, leverage Liquid for conditional logic, and initiate builds directly from a repository.

I realize that not everyone has the luxury of switching authoring tools, but when I made the switch, my company was a startup, and we had only three authors and a minimal amount of legacy content. I wasn’t burdened by a ton of documentation debt or cumbersome processes, so I could innovate.

Jekyll is just one documentation publishing option in the API doc space. I enjoy working with Jekyll’s code-based approach, but there are many different tools and publishing options to explore. That’s what we’ll dive into in this section.

Now that I’ve hopefully established that traditional HATs aren’t the go-to tools with API docs, let’s explore various ways to publish API documentation. Most of these routes will take you away from traditional tech comm tools more toward more developer-centric tools.

Video about publishing tools for API docs

If you’d like to view a presentation I gave to the Write the Docs South Bay chapter on this topic, you can view it here:

92/145 pages complete. Only 53 more pages to go.