Developer documentation trends — survey results

I recently conducted a survey about trends for those creating documentation for developers and engineers. You can view the content in several formats: slides, webinar, or article.

Slides

You can view the slides here:

Webinar

You can also view a recorded webinar where I talk through the results here:

Article

I wrote an article for the Institute of Scientific Technical Communicators (ISTC) magazine (Autumn 2020).

The same content from the PDF is available in HTML below:

Developer documentation trends: How developer documentation trends differ from general technical communication trends

Introduction

Despite excellent research on trends in the technical communication space, so far no survey has focused exclusively on trends within developer documentation only. By developer docs, I mean documentation written primarily for developers and engineers. Two recent surveys on the general tech comm space include Saul Carliner’s Tech Comm Census results (published in Dec 2018 STC Intercom) and Scott Abel’s Benchmarking Survey (summarized in the same issue).

Reading the results of these surveys, one would assume that most technical writers use Microsoft Word, Adobe FrameMaker, help authoring tools, CCMSs, and DITA. However, these surveys miss out on an important and sweeping tool change, often referred to as “docs-as-code,” that is taking place on the web. They also don’t explore many other trends within the developer doc space.

Scott’s survey does include some API-related information. He found that “Fifty-eight percent of technical communication teams surveyed say they currently document APIs; 10 percent plan to in the future.” One challenge tech writers face in documenting APIs is “using software tools not optimized for ease-of-use or writing efficiency, and lack of experience.” Scott’s survey also found that 21% of technical communicators use Markdown to create docs.

These responses about APIs are more relevant to developer docs, but they don’t go far enough. More developer-oriented topics are left out, such as how writers integrate with engineering Scrum teams, how writers interact with engineers on documentation, how writers handle the OpenAPI spec and other reference docs, and more.

Don’t get me wrong. I highly value these general surveys and the information they provide. But I was perplexed to see Adobe FrameMaker and Microsoft Word used so prominently. Admittedly, the tools usage reported by these surveys wasn’t too far off from previous WritersUA Tools surveys. For example, in 2014, WritersUA found that 52% of writers (199 out of 382 respondents) used FrameMaker (2014 WritersUA Tools Survey).

Reading these surveys made me wonder — is it really the case that so many tech writers are still using FrameMaker and Word? That didn’t match what I was seeing around me in Silicon Valley. But was I living in a bubble, an anomaly to the rest of the tech comm world? Were trends toward docs-as-code tools much more widespread and common in developer docs? The general tech comm surveys left me with more questions than answers.

A survey focusing on developer docs

To gather data about trends in developer docs, I decided to create my own survey. In the first developer documentation survey of its kind, I created a list of 50 questions, mostly multiple choice. I limited the audience to people writing docs for developers/engineers only. I promoted the survey on my blog, LinkedIn, and Twitter, and left the survey open for about two months, from January to March 2020.

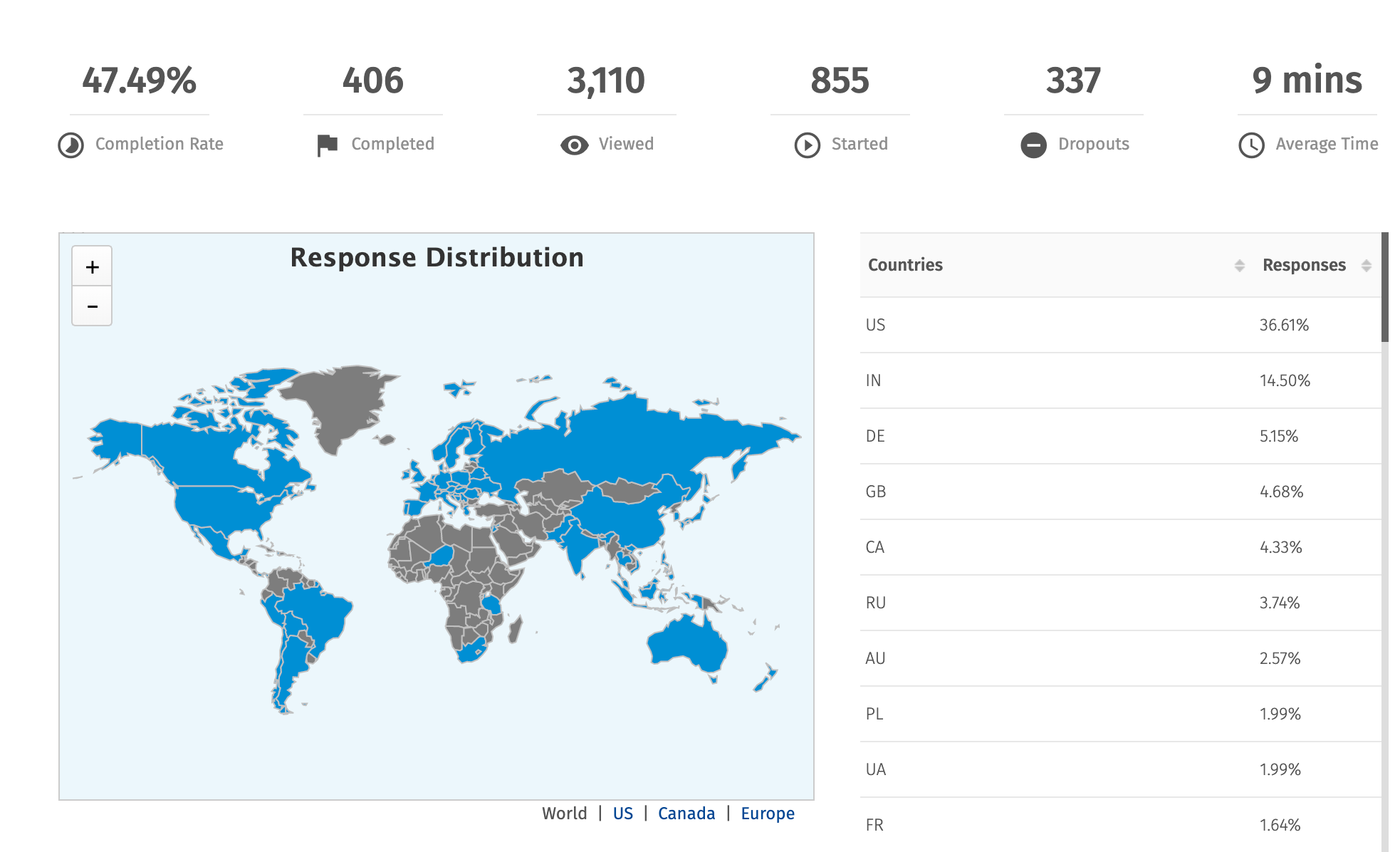

A total of 405 people completed the entire survey. Completing the survey means that after the 50th question, they clicked Submit. However, 855 started the survey, and 337 dropped out somewhere along the way. I allowed partial responses even if users dropped out along the way. So the actual number of respondents varied between 405 and 855, with some questions receiving more answers than others. About 37% of the respondents were in the US, about 15% in India, 5% in Germany, 5% in the UK, and smaller percentages from other countries.

You can browse the results of the survey directly at https://idratherbewriting.site/devdoctrendsreport.

Survey question categories

After the survey, to make better sense of the responses, I divided the 50 questions into five categories:

- Tool responses

- Formats and outputs responses

- Process and workflow responses

- API responses

- Profile responses

In the sections that follow, I’ll go through each section and provide summaries, highlights, and analyses. Percentages are rounded up or down. For more granular details, feel free to browse the survey results directly.

1. Tool responses

- Primary authoring tool: 22% static site generators (such as Jekyll, Hugo, Gatsby, Sphinx), 14% wikis, 11% XML tools, 8% HATs, 3% FrameMaker

- Text editor 25% Visual Studio Code, 19% Notepad++, 14% Atom

- Source format: 37% Markdown, 15% HTML, 15% XML

- Follow docs-as-code approach: 56% yes, 22% somewhat, 20% no

- Platform for publishing docs: 31% company’s own web servers or infrastructure, 15% GitHub Pages, 10% Gitlab

- Computer type: 54% Windows, 40% Mac

- How you manage content: 67% Git, 8% CMS, 5% CCMS

Summary and analysis:

In the dev doc space, tech writers don’t use a single tool for authoring, review, and publishing. Writers use different tools for different scenarios and purposes. For example, writers might use Confluence, Word, or Google Docs for early content development. When they transition the content into their authoring/publishing system, they work in Visual Studio Code or Atom as the text editor. Within these text editors, they usually write in Markdown formats with some YAML frontmatter.

Writers build the site output using a static site generator, such as Hugo, Jekyll, Sphinx, or MkDocs. To manage the content (for feature branches or to pull in work from others), they use Git. When it comes time to deploy the site build on a web server, they often have a continuous integration / continuous deployment (CI/CD) model that pushes the content onto GitHub, GitLab, or their company’s own infrastructure through a few keystrokes on the command line. This workflow is known as a “docs-as-code” approach because it treats documentation similar to how software developers treat code (to an extent).

Given this workflow, which would you say is the author’s “tool”? It’s unclear. The days when writers used an all-in-one purpose tool (for example, a single help authoring tool) for authoring, review, collaboration, and publishing are gone.

Complicating the tool question even more are writers who don’t have any tools outside their IDE, or integrated development environment (for example, IntelliJ IDEA). Some writers, usually engineers who are also writing docs, work only in code annotations and OpenAPI specifications. There is no “authoring tool.” For these writers, Markdown is their tool, as they might format annotations with Markdown and use scripts to export the Markdown into different systems. Many systems can import or export Markdown, making it a somewhat standard source format in this space (despite the many variants of Markdown flavors).

For examples of how multiple tools are used together in different combinations and solutions, see Jamstack examples. Jamstack refers to serverless websites built with JavaScript, APIs, and Markup and reflects modern web development trends. Jamstack excludes tools such as WordPress or other web apps that would require a heavy backend component on a server to run.

Overall, the survey results confirmed the predominance of the docs-as-code approach in the dev docs space. If you’re working with developer docs, this approach is trending. However, there’s also a decent amount of wikis, Oxygen XML, and MadCap Flare use, probably among those groups that have more robust localization and PDF requirements.

To read more thoughts about how source formats affect not just how we write but what we write, see my blog post, How you write influences what you write — interpreting trends through movements from PDF to web, DITA, wikis, CCMSs, and docs-as-code.

Formats and output responses

- Primary output: 72% HTML, 23% PDF

- Create video tutorials: 28% yes, 57% no, 14% plan to

- Docs plug into dev portal: 56% yes, 41% no

- Localize your docs: 73% no, 14% 1-3 languages, 10% 4+ languages

- Generate PDFs & distribute to audience: 57% no, 30% yes, 9% internal review only

- Significant role in developing publishing solution: 53% yes, 19% no

Summary and analysis:

Writers primarily create web content that fits into a larger developer portal. A developer portal is a centralized hub that serves as the home for many different sets of documentation. The developer portal might have a federated search, a login where developers can get API keys or make other configurations, and navigation to browse the different doc sets and products.

Writers often help shape and build the developer portal. They might help design the site, workflows, strategies for content re-use, stylesheets, etc. For example, a common task might be to brand the static-site-generated documentation to fit seamlessly into a React-based developer portal, as well as to define the Git workflows around content collaboration and publishing.

Localization, video tutorials, and PDF aren’t overwhelmingly produced in developer docs but do constitute about 25% of the output. The low amount localization eases up some pressure on the tools. If you don’t have to push your content into translation management systems, you aren’t as constrained with compatible format types and roundtrip workflows. (It’s still possible to localize with static site generators, just not as easy.)

I asked questions about video in the survey because I had heard negative comments about video formats from some developers. Additionally, a lot of developer docs consist of code, which might be tough to demonstrate in a video (you basically watch someone code in real time, which can be tedious and feel either too slow or fast for the audience). However, the survey found that most writers aren’t opposed to creating video content. The main reason for not creating video is due to lack of bandwidth, constantly changing technology, or because no one has asked for video — not necessarily because of an aversion for video.

Finally, the number of writers generating PDFs surprised me. It’s not so easy to generate PDFs from docs-as-code tools, especially for more long-form content with cross-references and other book-style formatting. However, PDF continues to be an important output, probably because there isn’t a good alternative for distributing content to beta partners prior to release. With docs-as-code tools, you don’t often have an authentication layer to gate the login. In these scenarios, sending partners a pre-release PDF is usually the easiest way to share content.

Process and workflow responses

- How do you interact with Scrum teams: 33% participate in limited capacity, 27% participate as full-fledged member, 19% have their own documentation Scrum

- How do you review docs: 25% code review tools, 19% in-person meetings, 14% collaborative annotation tools

- How do engineers contribute to docs: 31% pull requests, 31% wikis or similar, 22% direct repo rights

- Do you outsource docs offshore: 93% yes, 4% no

- Do you publish docs with CI/CD: 48% yes, 33% no, 15% plan to

- Do you have a style guide: 77% yes, 20% no

Summary and analysis:

Most writers participate on Scrum teams, sometimes in limited capacity; other times they have their own documentation Scrum teams. Scrum is the standard operating approach for most engineering groups (for better or worse), and technical writers plug into this rhythm for documentation as well.

Writers review docs often using the same tools engineers use to review code (e.g, code review tools that show diffs between commits). They also review docs through in-person meetings or through collaborative annotation tools like Google Docs.

The review process for docs has always been multi-pathed, and what works at one company might not work with another. Engineers often prefer to review content through code tools because it fits into how they’re reviewing code, so they’re accustomed to this approach. However, I find these tools exclude non-engineers, which weakens the review process — see my extended thoughts on this in Treat code like code and prose like prose.

Engineers contribute content either through pull requests to the doc source or by putting the content on a wiki or equivalent (for example, Google Docs, Quip). Other times engineers have direct rights in the repo to work with the content.

Note that the survey did not filter out documentation-writing engineers from dedicated technical writers. Many companies don’t have the luxury of technical writers, so engineers often play roles as documentarians. In these cases, it would be natural for engineers to have rights in documentation repos, or to store documentation in the same repos as the code. (See Integration documentation into engineering code and workflows for a summary of an engaging presentation about how Google’s internal doc team transformed their documentation by moving Markdown files directly inside of code repos.)

Outsourcing developer docs with an offshore authoring agency is rare. I did not ask for reasons why outsourcing isn’t more common, but there might not be many outsourcing agencies that can handle highly technical developer content. Or perhaps there are IP concerns about documenting the internal workings of APIs, or maybe the doc shops are so small that no one would manage an outsourced resource.

The publishing process for developer docs is streamlined through continuous integration and continuous deployment (CI/CD). This means writers can kick off builds and deployments with a few keystrokes on a command line. For example, if you set up a service on a specific branch, when you push changes to the branch, the service can start a build process on the server and then deploy the build onto a server. (For example, GitHub Pages offers automatic builds of Jekyll projects on any GitHub repository. You could also do this through Travis CI.) You can also run other verification scripts, such as link checkers, in an automated way.

Some hosting and deployment solutions like Netlify let you push out multiple builds, allowing you to create different environments for your content (alpha, beta, prod), with different conditions exposing different content in each environment. The automated publishing model is one of the biggest advantages of the docs-as-code approach. It allows you to constantly iterate on your content because the bandwidth for republishing requires such little effort.

Finally, most tech writers working with developer docs follow a style guide. It’s worth noting here that style guides for dev docs often take into consideration many elements of API design. Enforcing API styles (such as parameter casing or endpoint names) isn’t too different from doc style guides (where you enforce rules about title casing and verb forms). Arnaud Lauret’s The Design of Web APIs goes into this topic in detail — see API design and usability for a summary of key points.

4. API responses

- Documentation usually involves an API: 81% yes, 14% no

- Most common type of API: 56% REST APIs, 17% native library APIs (for example, Java, C++), 7% GraphQL, 7% SOAP

- Use OpenAPI docs for REST APIs 47% yes, 17% no, 16% sometimes

- Who generates the OpenAPI spec: 36% engineers, 26% both engineers and tech writers, 6% tech writers

- Who generates native library API docs: 32% engineers, 27% both engineers and tech writers, 6% tech writers

- Create OpenAPI spec manually or auto-generate it: 23% auto-generated, 22% manually, 22% both

- How to render OpenAPI spec into documentation: 27% Swagger UI, 17% internally built tools, 8% ReDoc

- Most common programming languages to know: 24% JavaScript, 17% Java, 16% Python

- Trending technologies you’re documenting: 13% machine learning, 11% artificial intelligence, 11% big data, 9% Internet of Things (IoT)

Summary and analysis:

Although the survey focused on developer documentation, not specifically API documentation, most developer docs involve some kind of API. As such, it’s fair to use developer documentation and API documentation somewhat synonymously, even if the latter is a subset of the former.

What kind of APIs are writers mostly working with? REST APIs, but only about half the time. Other times, writers work with native library APIs (such as Java or C++ APIs), GraphQL, or SOAP.

When documenting REST APIs, most teams use the OpenAPI specification. This is a detailed description of the API that follows a highly structured YAML or JSON format. Usually, either engineers create this spec, or engineers collaborate with tech writers on it. The same goes with reference documentation for native library APIs.

Reference docs have traditionally been written by engineers, so I imagine the collaboration here is usually one where writers edit the material rather than provide the annotations in source code. While engineers will often lead the charge with reference documentation, they rarely expand beyond this scope to tackle other elements of documentation, such as conceptual overviews, getting started guides, tutorials, how-to content, glossaries, troubleshooting, and FAQs.

In terms of processes for creating the OpenAPI spec, there’s a split between manually creating the spec and auto-generating it from annotations in the source code. The former approach embraces the spec as a blueprint or contract that engineers code against; the latter is used more by engineering documentarians who might be wary of documentation drift, or who find it more convenient to keep documentation together with code.

The OpenAPI spec alone isn’t readable documentation, but many tools can generate out documentation from the OpenAPI spec. The most common tools for this are Swagger UI, custom-built tools, or ReDoc.

REST APIs are language agnostic, but there are usually accompanying software development kits (SDKs) that are language-specific (companies provide them to help developers implement the API). The most important languages to know (likely because of the SDKs that accompany APIs) are JavaScript, Java, and Python. Outside of programming languages, trending technologies include machine learning, artificial intelligence, big data, and Internet of Things (IoT).

5. Profile information

- Age range: 17% ages 36-40, 16% ages 31-35, 14% ages 26-30, 12% ages 41-45, 11% ages 56-50, 11% ages 56-60, 8% ages 51-55, 4% 61-65 ages

- Gender: 52% male, 46% female

- Company: 200+ different companies listed

- College degree: 31% humanities, 28% engineering, 15% tech comm

- Satisfied with job: 38% agree, 37% strongly agree

- Team size: 34% lone writer, 31% team size 2-4 writers, 16% team size 8+ writers, 12% team size 5-7 writers

- Organizational model for tech comm: 40% centralized, 21% decentralized, 19% hybrid/distributed

- Employment type: 86% full-time, 10% contractor/vendor/temp

- Community you have most affinity towards: 39% WTD, 31% none, 14% STC

- Time spent learning to keep up: 28% 30 min/day, 27% 20 min, 14% 60 min

- Biggest challenges: technical know-how, time/bandwidth, getting reviews, addressing both novice and advanced users

Summary and analysis:

This final section covers profile and demographics data about the survey respondents. First to note is that the age range for writers in developer docs is fairly evenly distributed. This is reassuring given that ageism is a valid concern for senior workers in the technology industry. (Apparently, there are even resorts where aging tech workers in Silicon Valley go, some still in their 30s, to cope with anxiety about their increasing age.)

It seems the tech writer’s age is much less relevant, perhaps because this role is seen as supportive to engineers rather than a role where risk-taking is essential (as might be required for young tech entrepreneurs trying to disrupt larger companies). For an age comparison with developers, the 2020 Stack Overflow Developer Survey reports that the average age of developers (using Stack Overflow) is about 33.7 years.

The gender balance among dev doc writers is also reassuring. The Stack Overflow Developer survey found that 91.5% of their respondents were men, 8.0% women. Tech has a bad reputation for its “brogrammer culture.” In contrast, my survey found that the ratio for tech writers is 52% male / 46% female, which is much more balanced.

Another reassuring finding is that not everyone in this space is a former engineer. Instead, 31% have humanities degrees, 15% have technical communication degrees, and only 28% have engineering degrees. There’s often a presumption that to excel in developer docs, you need to be a former developer. Or if you are a former developer, you’re can automatically step to the front of the line. That doesn’t seem to be the case.

Job satisfaction is also strong, with 75% of people agreeing or strongly agreeing that they are satisfied with their jobs. Compare this with the 70% job satisfaction rate reported in Saul Carliner’s Tech Comm Census. Developer docs can be an intimidating space, where you’re frequently documenting code that’s hard to understand, where doc tools operate similar to software development tools, and where engineers have little patience to explain concepts to less technical people. Perhaps the job satisfaction is high because the salaries tend to be higher, the job market more abundant, and you’re in a space where you’re constantly learning.

Team sizes for writers in dev docs are small. A third are lone writers, and another third are on teams of 2-4 writers. Large teams of 8+ writers are less common, accounting for only 16% of respondents. Despite the small team sizes, 40% are centralized on a tech comm team within their company, while others are either decentralized (embedded and reporting directly within a product team), and others are in a hybrid model somewhere between centralized and decentralized.

As far as professional groups, more writers in this space have an affinity for Write the Docs, but many don’t have an affinity for any professional group.

Finally, the biggest challenges writers in dev docs face is having enough technical know-how to write docs and enough time/bandwidth to write it. Getting engineers to review docs is also challenging, as is creating content that addresses both novice and advanced groups.

Conclusion

The survey didn’t present any major surprises to the trends that I’ve already observed in this space. However, the answers provided more definitive data that confirms how different and unique developer docs are from other types of documentation. Technical writers transitioning into this space face a whirlwind of different tools, practices, and challenges. With this data, we can identify trends and see what standard practices are emerging. These trends can serve as a guide and reference as writers make their way in this space.

But also note that this space changes quickly. As JavaScript frameworks come and go, static site generators tend to follow suit, and what’s trending one year might fade the next. This is a plastic space where new technologies and experimentation can lead to overnight change.

About the author

Tom Johnson is a senior technical writer for Amazon in Sunnyvale, California. He is best known for his blog, I’d Rather Be Writing, where he posts regularly on technical communication topics. The blog has one of the largest followings of technical communicators online. Additionally, he has created an extensive web API documentation course at [https://idratherbewriting.com/learnapidoc/] that has helped hundreds of technical writers transition into API documentation.

Sources

- 2020 Developer Survey. Stack Overflow.

- Abel, Scott. Slides: The State of Technical Communication: 2019. The Content Wrangler.

- Abel, Scott. Survey Reveals Top Tools, Trends, and Technologies in Use in Technical Communication Teams. STC Intercom. Dec 2018.

- Abel, Scott. Webinar: The State of Technical Communication: 2019. The Content Wrangler. BrightTALK. Dec 13, 2018.

- Bowles, Nellie. A New Luxury Retreat Caters to Elderly Workers in Tech (Ages 30 and Up). New York Times. Mar 4, 2019.

- Carliner, Saul and Chen, Yuan. Job and Career Satisfaction Among Technical Communicators. STC Intercom. Dec 2018.

- Carliner, Saul and Chen, Yuan. Professional Development of Technical Communicators. STC Intercom. Dec 2018.

- Carliner, Saul and Chen, Yuan. What Technical Communicators Do. Carliner, Saul and Chen, Yuan. STC Intercom. Jan 2019. STC Intercom. Dec 2018.

- Carliner, Saul and Chen, Yuan. Who Technical Communicators Are: A Summary of Demographics, Backgrounds, and Employment. STC Intercom. Dec 2018.

- Johnson, Tom. API the Docs recording: How Trends in API Documentation Differ from other Tech Comm Trends

- Johnson, Tom. 2020 Developer documentation survey. Idratherbewriting.com. Dec 31, 2019.

- Johnson, Tom. Developer Documentation Trends — Survey Results

- Johnson, Tom. How you write influences what you write — interpreting trends through movements from PDF to web, DITA, wikis, CCMSs, and docs-as-code. Idratherbewriting.com. Feb 20, 2020.

- Johnson, Tom. Integrating documentation into engineering code and workflows. Idratherbewriting.com. May 26, 2015.

- Johnson, Tom. Treat code like code and prose like prose. Idratherbewriting.com. Jun 16, 2020.

- Johnson, Tom. API design and usability. Idratherbewriting.com.

- Lauret, Arnaud. The Design of Web APIs. Manning Publications. 2019.

- Welinske, Joe. 2014 WritersUA Tools Survey. WritersUA. Aug 20, 2015.

11/145 pages complete. Only 134 more pages to go.