How much code do you need to know?

With developer documentation roles, some level of coding is required. But you don’t need to know as much as developers, and acquiring that deep technical knowledge will usually cost you expertise in other areas.

- The ideal hybrid: programmer + writer

- Writers who learned to program

- Programmers who learned to write

- Wide, not deep understanding of programming

- Strategies to get by in deeply technical situations

- Techniques for learning code

- Is being a generalist a career disappointment?

The ideal hybrid: programmer + writer

When faced with these multi-language documentation challenges, hiring managers often search for technical writers who are former programmers to do the tasks. There are a good number of technical writers who were once programmers, and they can command more respect and competition for these developer documentation jobs.

But even developers will not know more than a few languages. Finding a technical writer who commands a high degree of English language fluency in addition to possessing in-depth technical knowledge of Java, Python, C++, .NET, Ruby, in addition to mastering docs tools to facilitate the authoring/publishing process from beginning to end is like finding a unicorn. (In other words, these technical writers don’t really exist.)

If you find one of these technical writers, the person is likely making a small fortune in contracting rates and has a near limitless choice of jobs. Companies often list knowledge of multiple programming languages as a requirement, but they realize they’ll never find a candidate who is both a William Shakespeare and a Steve Wozniak.

Why does this hybrid individual not exist? In part, it’s because the more a person enters into the worldview of computer programming, the more they begin thinking in computer terms and processes. Computers by definition are non-human. The more you develop code, the more your brain’s language starts thinking and expressing itself with these non-human, computer-driven gears. Ultimately, you begin communicating less and less to humans using natural speech and fall more into the non-human, mechanical lingo. (I explored this concept more in Reducing the complexity of technical language.)

This mental transformation is both good and bad — good because other engineers in the same computer mindset may better understand you, but bad because anyone who doesn’t inhabit that perspective and terminology will already be somewhat lost.

Writers who learned to program

When looking for candidates, would you rather hire a writer who learned programming, or a programmer who learned writing? There are pros and cons to each approach. Let’s first examine writers who learn programming, and then in the next section look at the reverse: programmers who learned writing.

In Enough to Be Dangerous: The Joy of Bad Python, Adam Wood argues that tech writers don’t need to be expert coders, on par with developers. Learning to code badly (such as is usually the case with writers who learn to code) is often enough to perform the tasks needed for documentation. As such, Wood aligns more with the camp of writers who learned programming. Wood writes:

You already know how hard it is to go from zero (or even 1) to actually-qualified developer. And you’ve met too many not-actually-qualified developers to have any interest in that path.

So how do you get started?

By deciding you are not ever going to write any application code. You are not going to be a developer. You are not even going to be a “coder.”

You are going to be a technical writer with bad coding skills. (Enough to Be Dangerous: The Joy of Bad Python)

Wood says tech writers who are learning to code frequently underestimate the degree of difficulty in learning code. To reach developer proficiency with production-ready code, tech writers will need to sink much more time than they feasibly can. As such, tech writers shouldn’t aspire to the same level as a developer. Instead, they should be content to develop minimal coding ability, or “enough to be dangerous.”

James Rhea, in response to my post on Generalist versus Specialist, also says that “adequate” technical knowledge is usually enough to get the job done, and acquiring deeper technical knowledge has somewhat diminishing returns since it means other aspects of documentation will likely be neglected. Rhea writes:

I wouldn’t aim for deep technical knowledge. I would aim for adequate technical knowledge, recognizing that what constitutes adequacy may vary by project, and that technical knowledge ought to grow over time due to immersion in the documentation and exposure to the technology and the industry.

I speculate that the need for writers to have deep technical knowledge diminishes as Tech Comm teams grow in size and as other skills become more important than they are for smaller Tech Comm teams. I’m not claiming that deep technical knowledge is useless. I’m suggesting that (to frame it negatively) neglecting deep technical knowledge has less severe consequences than neglecting content curation, doc tool set, or workflow considerations. (Adding Value as a Technical Writer)

In other words, if you spend excessive amounts of time learning to code, at the expense of tending to other documentation tasks such as shaping information architecture, analyzing user metrics, overseeing translation workflows, developing user personas, ensuring clear navigation, and more, your doc’s technical content might improve a bit, but the overall doc site will go downhill.

Additionally, while engineers can fill in the deep technical knowledge needed, no one will provide the tech comm tasks in place of a tech writer. As evidence, look at any corporate wiki. Corporate wikis are prime examples of what happens when engineers (or other non-tech writers) write and publish documentation. Some pages might be rich with technical detail, but the degree of ROT (redundant, outdated, trivial content) gets compounded, navigation suffers, clarity gets muddled, and almost no one can find anything.

Programmers who learned to write

Now let’s flip to the other side of the argument. What are the advantages of hiring programmers who learned writing? In contrast to Wood and Rhea, James Neiman, an experienced API technical writer, says that tech writers need engineering backgrounds, such as a computer science degree or previous experience as an engineer, to excel in API documentation roles.

Neiman says tech writers often need to look over a developer’s shoulder, watching the developer code, or listen to an engineer’s brief 15-minute explanation, and then return to their desks to create the documentation. You might need to take the code examples in Java and produce equivalent samples in another language, such as C++, all on your own. In Neiman’s view, API technical writers need significant technical depth to excel in this role.

Neiman and Andrew Davis (a recruiter for API tech writers in the Bay area) recently gave a presentation titled Finding the right API Technical Writer at an API conference in London. Their presentation format includes a Q&A exchange between the two. Scrub to around the 22-minute mark for the relevant part:

Here’s a transcript of two questions in their exchange (cleaned up a bit for readability):

Andrew: What is essential to your relationship with each new client?

James: Being part of the product team, what’s essential is communication within the team. Communication is essential to keep up with what is changing (and I expect things to change very rapidly, especially in a disordered environment where people are trying to stand up a product). I also need to earn and retain trust.

Why should I say that? If I’m going to be sitting with an engineering team, I’ll need them to let me into their source code so I can modify their source code comments. I’ll need to be able to pick an engineer’s brain for fifteen minutes and fifteen minutes only — and get meaningful information out of that interview so that I can go and produce the documentation they need and get it right the first time. If I don’t get it right the first time, I’ve wasted the engineer’s time, and I’ve wasted the company’s money.

Andrew: Can a tech writer without a development background write great API documentation?

James: Absolutely not. There is no way that a busy engineering team has time to train a person without a computer science degree. That’s just the reality of it. Engineers at best can speak to you in some version of English, which may or may not be their native language. They don’t have a lot of time, and they expect you to finish their thoughts for them. That means that you need to be able to sit next to them and look at how they’re coding, and then be able to replicate that and extend it and even create examples.

They may say, “Here’s an example. You can extend it, add on these other APIs, work out this use case for us. We haven’t had time to finish this.” They can say, “Well, let me show you how this works in Objective C; we also support this on Java. Can you create something similar on Java?”

If you don’t have that kind of development background, it’s unrealistic that you could expect to train, for example, somebody with a masters degree in English (and who is a very intelligent person but otherwise not technical) to do such a thing.

Keep in mind that Davis and Neiman are trying to persuade more European countries to use Synergistech as their recruiting agency to find and hire API tech writers, so they’re presenting the need for engineering-savvy tech writers. These super tech-savvy writers are harder to find — hence the need for expert recruiters. Regardless of the agenda, Neiman and Davis argue for a higher level of coding proficiency than Wood or Rhea.

The level of coding knowledge required no doubt depends on the position, environment, and expectations at your company. Perhaps if the tech writer doesn’t have more of an engineering background, engineers will just send the tech writer code snippets to paste into the docs. But without the technical acumen to fully understand, test, and integrate the code in meaningful ways, the tech writer will be at the mercy of engineers and their terse explanations or cryptic inline comments. The tech writer’s role will be reduced to being an editor/publisher instead of a writer.

In my experience, Neiman’s explanation about developers instructing tech writers to create similar code in other languages (based on a 15-minute over-the-shoulder conversation at the engineer’s desk) goes too far. Although I’ve created simple JavaScript code samples (based on a pattern the engineers showed me), I’ve never been asked to create code samples across other languages. I could auto-generate code snippets for web API requests (using Postman), but to develop code across multiple languages tends to be more of the programmer’s responsibility, not the tech writer’s.

Neiman goes on to say that in one company, he tested out the code from engineers and found that much of it relied on programs, utilities, or other configurations already set up on the developers’ computers. As such, the engineers were blind to the initial setup requirements that users would need to run the code properly. Neiman says this is one danger of simply copying and pasting the code from engineers into documentation. While it may work on the developer’s machine, it will often fail for users.

This comment from Neiman does ring more true to me. As I argued for extensively in Testing your API documentation, you have to be able to test the endpoints, code samples, and SDKs in order to write and evaluate the documentation. It is usually true that programmers (who set up their machines months ago) have long forgotten or can’t even identify all the frameworks, configurations, and other utilities they installed to get something working. The more technical you are, the more powerful of a role you can play in shaping the information.

Neiman is a former engineer and says that during his career, he has probably worked with 20-25 different programming languages. Being able to learn a new language quickly and get up to speed is a key characteristic of his tech comm consulting success, he says.

But in this celebration of technical knowledge, companies make a mistake and assume that these programmers-turned-technical writers can easily handle writing tasks, because c’mon, everyone can write, right? However, without a stronger writing background, these programmers who are now writing might be a lot less proficient in areas where it really matters.

For example, recently I was working with an engineering team on a new voice feature for our product. The engineering team was partly based in India and other places, and they frequently met (during India business hours) to shape a document about the new voice feature. This documentation and the feature were in constant flux, so the team kept iterating on the content over the course of about two weeks after meetings with stakeholders, solutions architects, and other reviewers. After each review, the team sent me the document to edit and publish it for stakeholder reviews.

I wasn’t directly embedded with the team, nor was I a dedicated resource for the team. In this role, I simply acted as editor and publisher. But I had to turn around the gibberish they wrote at a rapid rate, usually in 1-2 hours. As this project was one of many I was juggling, I had to quickly restructure and rewrite the content (sometimes touching every sentence) to make it read like a native speaker had written it rather than engineers in another country. During this same time, I was working on rewriting our team website and other writing projects.

I have a tech writing colleague who is a former engineer, and I often wonder if he has the same writing skills to edit this content with the same speed and efficiency that I do. Of course, I shouldn’t make judgments, but I’m pretty good at both writing and editing. After all, look at the output on my blog. In just a couple of hours during the evening, I can write a post that is worth reading in the morning. Can engineers who lack writing backgrounds do this? If tech writers are increasingly playing publishing/editing roles instead of developing content directly (because the content is so highly technical that only specialists can create it), then shouldn’t companies prioritize writing abilities over technical abilities (to an extent)?

Further, companies who assume that “everyone can write” fail to distinguish the different levels of writing. It’s one thing to write coherent sentences in a paragraph or even a single topic, but can the writer read over 20 pages in a documentation system and ensure consistency across all the topics? Can the writer weave together workflows and journeys across these larger systems? Can the writer distill information from a long, complicated process into an intelligible quick reference guide? Writing skills fall along a spectrum, and while most professionals appear somewhere on the spectrum, their skills might not be enough to excel in ways that provide deeper value for documentation.

Overall, technical writers of all stripes are playing generalist roles in increasing ways, and in these generalist roles, strong writing skills rather than specialized knowledge might be more important. For sure, a combination of the two skills — writing and technical expertise — tends to be a knockout punch in the job market.

For an in-depth analysis of the dilemma between being a generalist or specialist, see my essay Be both a generalist and specialist through your technical acuity in my Simplifying Complexity series.

Wide, not deep understanding of programming

Let’s settle the question about the best candidate to hire by finding some middle ground between the two extremes. Clearly, tech writers need to understand code, but they probably don’t need to be engineers to the extent that Neiman argues (writing their own code in other languages).

Although you might have client implementations in a variety of programming languages at your company, the implementations will be brief. The core documentation needed will most likely be for the REST API, and you will have a variety of reference implementations or demo apps in these other languages.

You don’t need to have deep technical knowledge of each of the platforms to provide documentation. You’re probably just scratching the surface with each of these client SDKs. As such, your knowledge of programming languages has to be more wide than deep. It will probably be helpful to have a grounding in fundamental programming concepts and familiarity across a smattering of languages instead of in-depth technical knowledge of just one language.

Having broad technical knowledge of multiple programming languages isn’t easy to pull off. As soon as you throw yourself into learning one language, the concepts will likely start blending together.

And unless you’re immersed in the language on a regular basis, the details may never fully sink in. You’ll be like Sisyphus, forever rolling a boulder up a hill (learning a programming language), only to have the boulder roll back down (forgetting what you learned) the following month.

Full immersion is the only way to become fluent in a language, whether referring to programming languages or spoken languages. As such, technical writers are at a disadvantage when it comes to learning programming. To get fully immersed, you might consider focusing on one core programming language (like Java) and only briefly playing around in other languages (like Python, C++, .NET, Ruby, Objective C, and JavaScript).

Of course, you’ll need to find a lot of time for this as well. Don’t expect to have much time on the job for actually learning a programming language. It’s best if you can make learning programming one of your “hobbies.”

Strategies to get by in deeply technical situations

Suppose you find yourself deep in APIs that require you to know a lot more technical detail than you currently do (despite your programs of study to learn more)? How can you get by without a deeper knowledge of programming?

Keep in mind that your level of involvement with editing, publishing, and authoring depends on your level of tech knowledge. If you have a strong knowledge of the tech, you can author, edit, and publish. If you have weak tech knowledge, your role might involve publishing only. The following spectrum diagram illustrates this range of involvement:

If you’re stuck in the publishing/editing area, you can interview engineers at length about what’s going on in the code (record these discussions — Evernote has a nifty recording feature built-in that I’ve used multiple times for just this purpose), and then try your best to describe the actions in as clear speech as possible. You can always fall back on the idea that for those users who need Python, the Python code should look somewhat familiar to them. Well-written code should be, in some sense, self-descriptive in what it’s doing. Unless there’s something odd or non-standard in the approach, engineers fluent in code should be able to get a sense of how the code works.

In your documentation, you’ll need to focus on the higher-level information, the “why” behind the approach, highlighting of any non-standard techniques, and the general strategies behind the code. You can get this why by asking developers for the information in informational interviews. The details of what will either be apparent in the code or can be minimized. (See Code samples and tutorials for details.)

As you decide how much detail to include, remember that even though your audience consists of developers, it doesn’t mean they’re all experts with every language. For example, the developer may be a Java programmer who knows just enough iOS to implement something on iOS, but for more detailed knowledge, the developer may be depending on code samples in the documentation. Conversely, a developer who has real expertise in iOS might be winging it in Java-land and relying on your documentation to pull off a basic implementation.

More detail in the documentation is always welcome, but you can use a progressive-disclosure approach so that expert users aren’t bogged down with novice-level detail. Expandable sections, additional pages, or other ways of grouping the more basic detail (if you can provide it) might be a good approach.

There’s a reason developer documentation jobs pay more — the job involves a lot more difficulty and challenges, in addition to technical expertise. At the same time, it’s just these challenges that make the job more interesting and rewarding.

Techniques for learning code

The diversity and complexity of programming languages is not an easy problem to solve. To be a successful API technical writer, you’ll need to incorporate a regular regiment of technical study. You always have to be learning to survive in this field.

Fortunately, there are many helpful resources (my favorite being O’Reilly’s Safari Books Online). If you can work in a couple of hours a day, you’ll be surprised at the progress you can make.

The difficulty of learning programming is probably the most strenuous aspect of API documentation. How much programming do you need to know? How much time do you spend learning to code? How much priority should you spend on learning technology?

For example, do you dedicate two hours a day to learning to code in the particular language of the product you’re documenting? Should you carve this time out of your employer’s time, or your own, or both? How do you get other doc work done, given that meetings and miscellaneous tasks usually eat up another 2 hours of work time? What strategies should you implement to learn code in a way that sticks? What if what your learning has little connection or relevance with the code you’re documenting?

In a post called Strategies for learning technology – podcast recommendation and a poll, I linked to a 10-minute Tech Comm podcast with Amruta Ranade on Learning New Technology and then polled readers to learn a little about their tech learning habits. In the reader responses, most indicated that they should spend 30-60 minutes each day learning technology, but most spend between 0-20 min actually doing so. To learn, they use general Google searches. They mostly devote this time to learning tech at work, though some split the time between work at home.

Personally, I think spending 20 minutes a day isn’t enough to keep up with the knowledge needs. Sixty minutes is more appropriate, but really, if you want to make progress, you’ll need to devote about twice that time. Finding 1-2 hours of time (and motivation) at work to learn it is unlikely. I always feel like I’m not getting enough done as is during work hours — learning technology often feels like a side activity taking me away from my real duties.

Also, the information I need to document in the present moment is usually too advanced to simply learn from watching tutorials on Safari Books or other sources. But I can’t just start out consuming advanced material. I have to ramp up through the foundational topics first, and that slow ramp-up feels like a tangent to the real work that needs to get done.

For example, you might need to document the equivalent of Advanced Calculus concepts. But to ramp up on Advanced Calculus, you need to build a foundation with Trigonometry and Algebra. When you spend time studying Trigonometry and Algebra instead of the Advanced Calculus concepts that you need to document, it can feel like you’re not making any progress on your documentation.

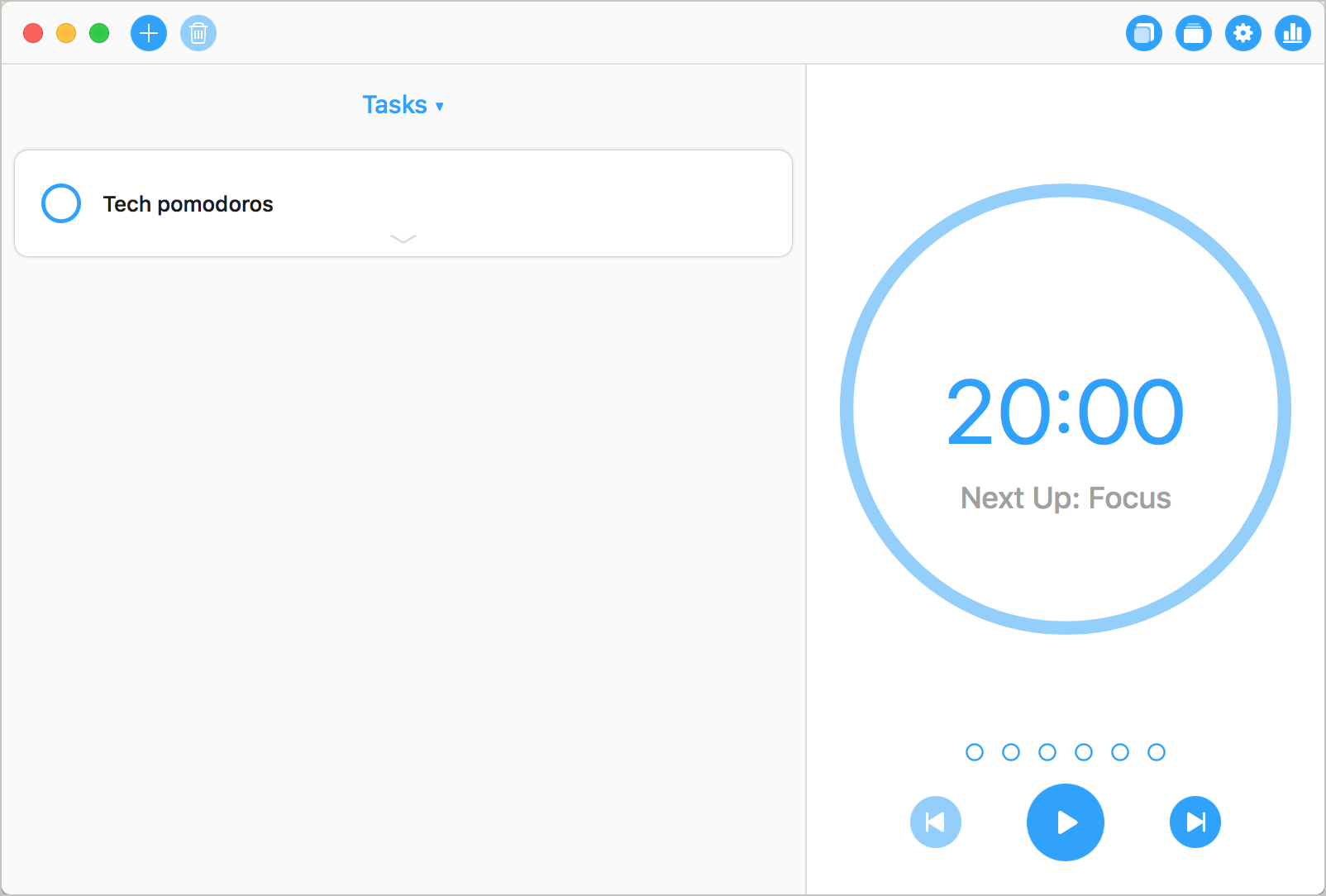

One strategy I’ve found to work well is to divide the learning into “pomodoros” (a technique named after tomato kitchen timers). With the Pomodoro Technique, you set a timer for 20 minutes and focus on your learning task for that chunk of time. You can set a goal to complete as many pomodoros a day as you want. After about 1-2 months of these regular pomodoros, you’ll be surprised at your progress. I use the Focus app for my pomodoro timer:

Additionally, I recommend keeping a list of notes about technical details you struggle with while you’re trying to document something, and then during your pomodoros, focus on what’s listed in your technical notes.

Even so, this pomodoro technique for focus doesn’t solve the problem. It’s still hard to squeeze time in for the pomodoros. Whenever I squeeze these into my life, I end up squeezing other activities out.

There are a lot of questions about just how to learn code, and I don’t have all the answers. But here’s what I know:

- Developer documentation requires familiarity with code, though exactly how much expertise you need is debatable.

- You have to understand explanations from engineers, including the terms used. The explanations in your documentation should focus on the why more than the how.

- You should be able to test code from engineers so that you can identify assumptions that engineers are often blind to.

- To thrive in an API documentation career, you have to incorporate a regiment of continual learning.

- Completing several pomodoros a day over the course of weeks and months can result in significant progress in building your technical understanding.

Is being a generalist a career disappointment?

Technical writers will likely be generalists with the code, not good at developing it themselves but knowing enough to get by, often getting code samples from engineers and explaining the basic functions of the code at a high level.

Some might consider the tech writer’s bad coding ability and superficial technical knowledge somewhat disappointing. After all, if you want to excel in your career, usually this means mastering something thoroughly, right? You want to be an expert in your field.

It might seem depressing to realize that your coding knowledge will usually be kindergartner-like in comparison to developers. This disparity positions tech writers more like second-class citizens in the corporation. In a university setting, it’s the equivalent of having an associates degree where others have PhDs.

However, take consolation in the fact that your job is not to code but rather to create helpful documentation. Creating helpful documentation isn’t just about knowing code. There are a hundred other details that factor into the creation of good documentation. As long as you set your goals on creating great documentation, not just on learning to code, you won’t feel entirely disappointed in being a bad coder. This perspective doesn’t address all the issues, but it does provide some consolation at the end of the day.

For more information about working with code, see these two topics:

Let’s look at one more topic in this jobs section: Locations for API doc writer jobs.

111/145 pages complete. Only 34 more pages to go.