What research tells us about documenting code

Before diving in to how to document code, let’s first explore some research that has been done on best practices for documenting code, as this can inform our direction and approach. A couple of academic articles stand out as noteworthy for this effort:

- “When Not to Comment: Questions and Tradeoffs with API Documentation for C++ Projects” by Head et al. This article explores how developers at Google find and use documentation for code. The researchers found that for simple code, sometimes developers prefer to examine the code directly. However, for more complex code, developers consult the code’s documentation, often by looking in the formal class declarations for information they need; other times they look at comments in the implementation code. Besides providing guidance on the best location for documentation, the researchers also identify what type of answers and guidance developers want for the content of the documentation.

- “How Developers Use API Documentation: An Observation Study” by Meng et al. In this article, the researchers look at how developers interact with API documentation and found a mix of both systematic (read-first, explore-later) and opportunistic (explore-first, read-later) learning styles. While we often write with systematic developers in mind, focusing on opportunistic behaviors might be more beneficial, and will cause us to look more closely at improving search, navigation, interactive components, troubleshooting, error messages, and other action-oriented features.

Both of these articles come from academic journals. It’s actually rare to find research about API documentation in academic journals (not sure why), and when you do find them, they’re often in engineering or computer science journals (rather than tech comm journals). Later I’ll dive into some articles outside of academic journals.

- When Not to Comment: Questions and Tradeoffs with API Documentation for C++ Projects

- How Developers Use API Documentation: An Observation Study

- Takeaways from the Research

When Not to Comment: Questions and Tradeoffs with API Documentation for C++ Projects

First, let’s explore “When Not to Comment: Questions and Tradeoffs with API Documentation for C++ Projects,” by Andrew Head, Caitlin Sadowski, Emerson Murphy-Hill, and Andrea Knight. This article was published in the 2018 ACM/IEEE 40th International Conference on Software Engineering. (To read the article, see this ResearchGate link or go here.)

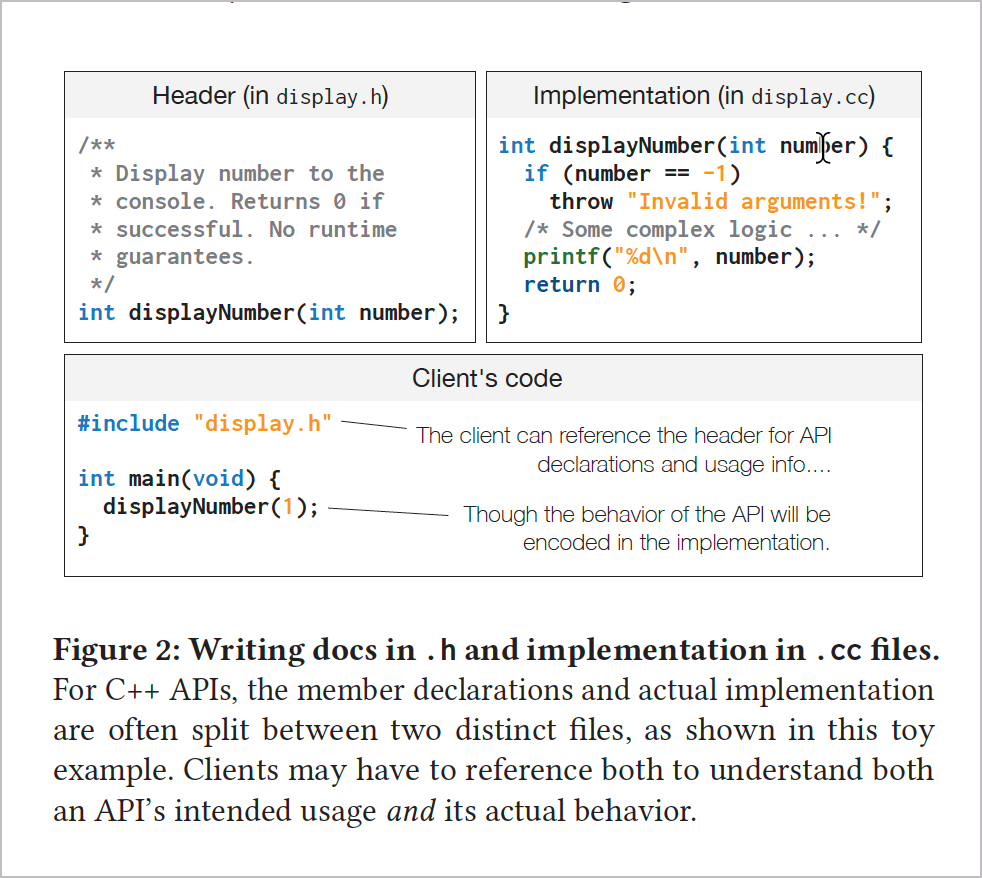

This research coordinates efforts among academic researchers, engineers, usability specialists, and members from Google’s Engineering Productivity Research team. Given how important documentation is for understanding code, the researchers want to know the best location for documentation as well as what information engineers want in docs. Specifically, they focused on C++ APIs and asked whether engineers are more inclined to consult the header files (where classes are defined) or the implementation files (where classes are implemented) for the information they need. The following screenshot (from their article) shows the difference between header and implementation files:

Basically, in C++, the header files (.h) contain the classes and the main documentation. The implementation files (.cc) instantiate and implement the classes from the header files. In short, the header files contain more formal documentation that follows specific annotation conventions, while the implementation files contain the guts of the logic about how the class has been implemented. Implementation files have comments peppered inline with the code, without formally structured doc annotations. A central question the researchers wanted to know is whether users gravitate toward the inline code comments in implementation files or the official documentation in the header files.

The researchers used tracking tools to identify when developers would switch from one type of file to another, and they also interviewed the developers as a follow-up. Google has about a billion lines of code stored in a central code repository that can be used across the company, so thousands of developers might find and discover code in this monorepo to use in their projects. The team that uses an API might not know the team that developed the API, and vice versa.

Even if you don’t document C++, this study is helpful because it raises this central question: should you put the bulk of your documentation in formal descriptions about the code, or should the bulk of your documentation appear within the context of the code, peppered in as inline comments.

After gathering information from more than 600 participants in their study, the researchers found that not all code is equal. Complex code needs more formal documentation, but simple code might not need documentation at all.

What type of code actually needs documentation

First, the researchers found that most developers actually looked in the header files for documentation:

Survey respondents reported it would be most convenient to find answers to many of these questions in header files, though interviewees indicated code could be accurate and quick enough to read in many cases.

But the researchers also found that for simpler APIs, many developers read the code directly (rather than consulting the docs) to see if they can quickly understand the API. In other words, they see if they can figure out what’s going on by looking solely at the code.

Some developers actually have philosophical views about distrusting the accuracy and currency of documentation and prefer to view the code as the primary source of information, like reading a primary source instead of secondary or tertiary sources of information. As many developers who distrust docs know, documentation for code can easily become outdated and neglected, so why trust it? Why even bother to read it?

In fact, some developers feel that documentation for simple code becomes a liability and a hindrance for development. The doc gets in the way of the developer’s path to simply reading the code and understanding it on its own terms.

Besides skipping docs when the code is simple enough to understand on its own, the researchers also recommend avoiding writing docs while development is in constant flux (because it makes documentation a constantly evolving target). The researchers say you might also consider skipping writing docs when there aren’t sufficient resources to keep the documentation updated. When maintainers can’t keep the documentation up to date, it “rots” and becomes more of a liability.

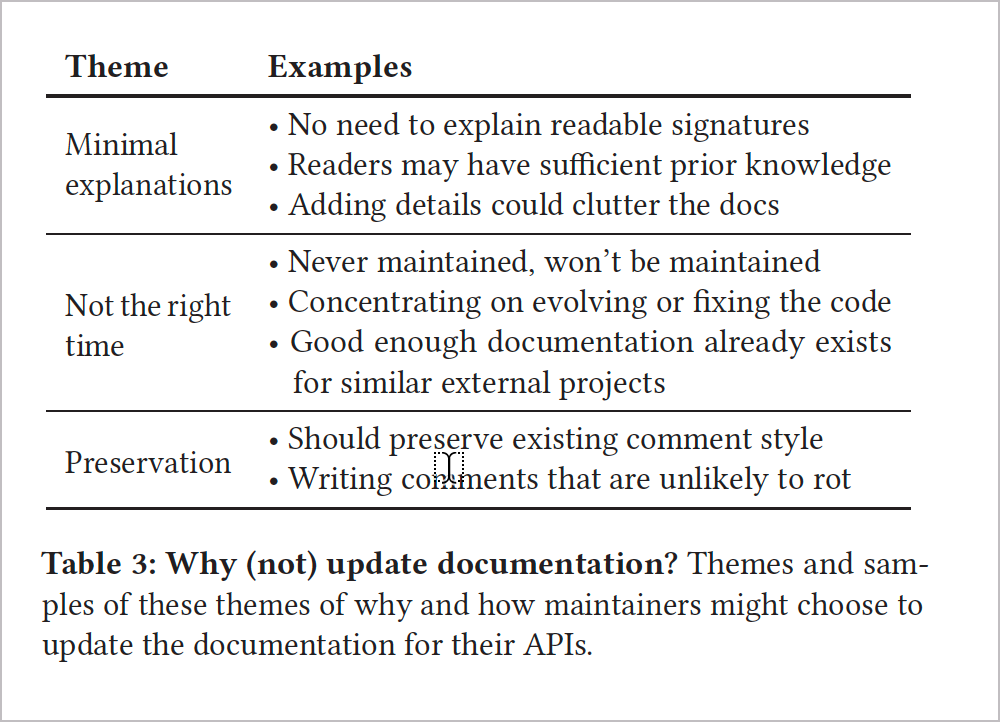

In short, there are valid arguments for not even writing documentation, particularly for simple code. The following chart shows when documentation might not be necessary with code:

However, for more complex code, especially where multiple files and generated code might be involved, developers still relied on the formal documentation to understand it. The researchers explain:

When isn’t code enough to be self-documenting? Sometimes, developers had no problem reading code, and in fact preferred it for finding more accurate information. However, there are some cases where self-documentation isn’t feasible, like code with overly complex method signatures and generated code. Other details, like recommended usage, just can’t be conveyed by source code.

In short, when the source code isn’t intuitive to understand on its own, developers turned to more lengthy and formal documentation about it. This makes sense and aligns with best practices for GUI documentation as well — one should always focus on the complicated parts of a system, not the obvious elements that no one needs help with.

Granted, recognizing what code is simple versus complex is the challenge because the technical writer is likely not a developer and will likely only have a rudimentary idea about the complexity of the code. Just because the code is short or long does not give a clear indication about its complexity. A short snippet out of context might be confusing, while a lengthier sample that contains a fully functioning sample might be more understandable.

As an analogy, an outsider visiting a city in a faraway country. The outsider wouldn’t know whether some observed event is normal or out of the ordinary — you have to be more familiar with the place to gauge whether an event is strange or commonplace. Same with code.

You could ask the developers about the level of complexity of the code, but this assumes that you can trust the judgment of the engineers who designed and created the code (unless you’re asking engineers on other teams). Developers almost always overestimate the level of intuitiveness of the code they wrote and assume more capability in their audience than the audience actually has. How many times have you heard engineers say, “Users will understand this — and if they don’t, they shouldn’t be using the API.” But are the risks of omitting docs greater than the risk of including them?

More advanced developers can probably extrapolate the API’s usage from code, while beginning developers might need more handholding. Do comments interfere with readability for advanced developers but aid readability for new developers? Are we doomed to frustrate one audience in order to help another? And is there a greater risk in omitting documentation than in overburdening docs with too much explanation?

When to document code

Let’s set aside questions about whether to document or not and focus instead on timing for writing docs. The researchers found that there’s an ideal time for writing and updating documentation:

The ideal time to propose changes to documentation is during code authoring and review, possibly through a surrogate like a code reviewer. Documentation can get updated only infrequently after it is initially written, as future updates may raise questions of whether the information adds clutter or redundancy.

In other words, write the docs when the code development is still fresh in the developer’s mind. If you wait too long after active development finishes, the documentation will likely be neglected and forgotten, as developers move on to other projects.

Of course, timing is not always easy to plan. Your availability might not match up with the developer’s coding sprints. You’re probably juggling several other projects with more pressing timelines, and so you might have to postpone this documentation until one or two months post development. But by that time, the developer may have long ago finished coding and forgotten many details. The nature of complexity is that we hold a plethora of details in our heads (in our short-term memory) while we’re elbow-deep in the task, but once we move on, our brains dump the information from short-term memory so that we can load up our brain’s RAM with another project.

If you try to prod developers to articulate details no longer at the forefront of their minds, they might not have forgotten it, but their motivation and enthusiasm to explain it and review your docs will likely be poor. They have already moved on. Strike while the iron is hot.

With a recent project I documented, the documentation was mostly written post-release of the product. The initial version had been written by a product manager, and later, after many complaints about the poor quality of the docs, tech writers had been called in to fix it. But months after the product had been released, the team was no longer meeting in regular sprints, engineers were focused on other matters, and it seemed no one had interest in explaining things to tech writers nor reviewing documentation.

There is a right moment to jump into a documentation project — that time is usually pre-release. But just as one can jump in too late and miss out on enthusiasm and availability, jumping in too early can also prove inefficient. You might find that plans are high-level; nothing has actually been coded yet, or ideas are scrapped from one sprint to the next. It might be like trying to document a recipe while cooks are still deciding on the ingredients.

Regardless of whether you can actually do anything about the timing, you should have in mind that timing is a noteworthy element in documenting code. Code is not a standalone artifact independent of time. Time is a relevant factor that determines your ability to document code.

What questions to address in code documentation

So far we’ve looked at where code documentation should appear and when code documentation should be written. Now let’s look at code documentation from another angle: what types of answers and guidance should be in the documentation. This is a more difficult, broad question, and the researchers’ answer is “API usage.” They write,

Most searchers and maintainers we interviewed had opinions about what did belong in documentation, at both the level of headers and in-line comments. Maintainers and searchers mentioned the importance of describing how a file relates to other files in the project (S17), the state of the world when a method is called (S8), executable examples (M5, M8), implementation comments for future maintainers of an API (M5), explicit links to external documentation (M5), semantics of a function (M8), main concepts that someone should understand and know to use the API (M8), “what” the code is doing and “why” at a statement level (M6), and even a proof of correctness (M6). It is unsurprising that not all of this information was available for all of the APIs we saw during this study.

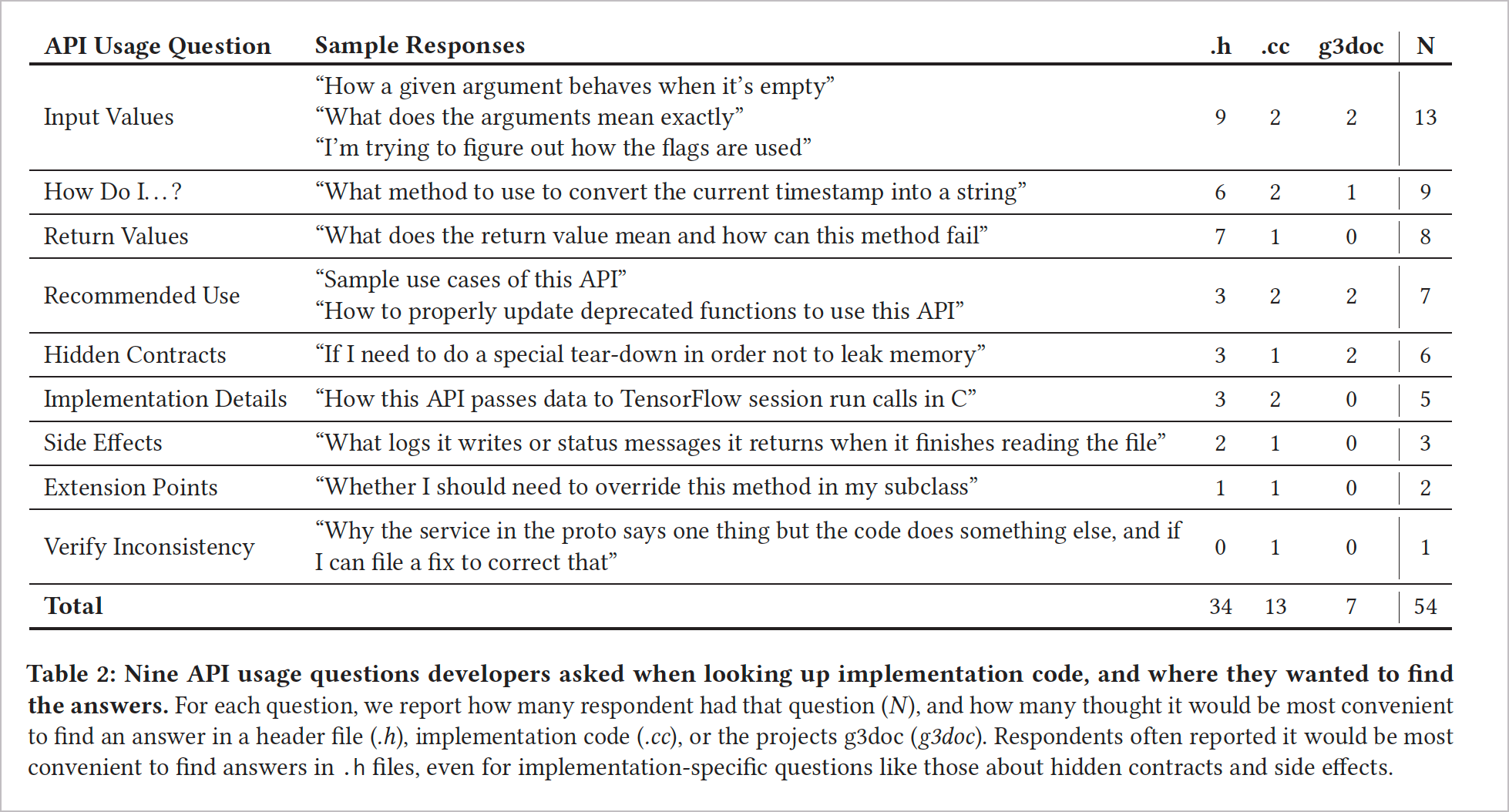

The researchers arrange this information into a chart for readability:

Nothing particularly stands out here, except that “input values” are read the most. Input values refers to parameters or other arguments that developers often consult to understand data types, casing, or other details. As such, take pains to document your parameters in great detail. I describe the various categories to cover at length with parameters in Step 3: Parameters. With REST APIs, some details to note about parameters might include the following:

- For REST API endpoints, the type of parameter: header, query string, and path. Also consider request bodies.

- Default values

- Min or max values

- Data types (boolean, integer, string, etc.)

- Sample values

Other callouts about content include “How do I?…” questions. In other words, rather than just reading reference information, developers want instruction that explains how to implement the reference topics toward a business goal or end. Just as with end-user (GUI) documentation, focusing on tasks rather than simply defining reference information remains an important element of code documentation. Most technical writers already orient their mindset around task-based documentation, so this focus needs no expansion here.

Finally, “Recommended Use” is also an interesting element to surface. “Recommended” paths aren’t that common in GUI documentation — users usually have a task, and there’s a preferred way to achieve it. But with developer docs, there are often a dozen ways to go about a goal, and just because code compiles does not mean it is good. Code needs to scale, be efficient, and cover a multitude of use cases. Therefore, recommendations are in order to help guide a developer down many potential paths of documentation.

In fact, this might be a defining characteristic that separates GUI documentation from developer documentation. GUI documentation typically has a single path to achieve a result. Developer documentation, on the other hand, is more like providing a cabinet of baking goods to put at the developer’s disposal — salt, flour, baking powder, eggs, vanilla, baking soda, spices, and so on. The developer might choose to use one API here, another there, some in combination with each other, all to achieve a particular end. That particular end is more open and flexible depending on what the developer is building/baking. (One difference here is that developers don’t typically eat their code.)

Conclusion

Overall, this research has many insights and conclusions. The article addresses many concerns around code documentation and presents a complex view about each of these facets — when/if to document code, where to put this documentation, when to write the documentation, what questions to address, and more. There’s not always a clear path to follow (it’s messy), and many environmental, product, and audience details must factor into the documentation strategy. Still, this article provides solid research and probes the topic in illuminating ways.

How Developers Use API Documentation: An Observation Study

Now let’s move into another meaty academic article that addresses best practices for documenting code. The January 2019 issue of Communication Design Quarterly, a publication of SIGDOC (the Special Interest Group for Design of Communication), features an article called How Developers Use API Documentation: An Observation Study. Several researchers from Merseburg University in Germany — Michael Meng, Stephanie Steinhardt, and Andreas Shubert — set out to “understand how developers use documentation when starting to work with a new API.”

For their research, they “asked software developers to solve a set of pre-defined tasks using a public API unfamiliar to them on the basis of the documentation published by the API provider” — and then observed their behavior. Basically, these users had to figure out how to construct REST API requests with the right parameters and other configurations in order to send requests that would return the needed information. The researchers then observed how the developers used the API documentation to figure out the tasks.

There are a lot of great observations and conclusions in this article. I’m just summarizing and highlighting the information here. I recommend that you read the article for the full details.

Systematic versus opportunistic behaviors

The authors present some previous research about systematic and opportunistic learning behaviors. These terms are typically how previous researchers describe the contrasting user behaviors.

You’re undoubtedly familiar with these two types of behaviors. Sometimes when you get a new device, you just start pushing the buttons and exploring how it works based on inputs and responses, trial and error, etc.. — this is called “opportunistic” behavior. Other times you might crack open the user guide and start reading from page one before pushing buttons on the device — this is called “systematic” behavior). Other times you blend the two modes (“pragmatic” behavior). Same with developers using an API.

The authors describe the opportunistic behavior patterns in their study as follows:

… [opportunistic] developers worked in a more intuitive manner and seemed to deliberately risk errors. They often tried solutions without double-checking in the documentation whether the solutions were correct. For example, P10 [person 10] changed parameter values to values that seemed to match based on experience with similar problems, but he did not check in the documentation whether the values were actually correct or even existing. P2 [person 2] inserted parameters that he had noticed at some point in the documentation before, but did not attempt to re-consult the relevant section of the documentation to make sure that the parameters were spelled correctly. …

We found that opportunistic developers in our test started the first task with some example code from the documentation which they then modified and extended. Once a task was completed, the piece of code that solved the task was used as starting point for the next task, which again was a potential source of error. Developers in this group worked in a highly task-driven manner, but also tried things that were not related to the task, but possibly helped them to build a broader understanding of the API in passing. For example, P9 [person 9] submitted a request for a UPS service (United Parcel Service) which was not required by any of the tasks, simply in order to see what would happen.

We noted that developers which we assigned to the opportunistic group did not take time to get a general overview of the API before starting with the first task. They scrolled briefly through some pages of the documentation, checked the tools available and then started with the first task. Developers from the opportunistic group wanted fast and direct access to information. They did not systematically read larger sections of the documentation, but typically searched for a specific piece of information and then scanned the documentation.

In short, opportunistic developers learn by doing. They look at a piece of code, try it out, experiment with parameters, see what gets returned in the response, and more. They learn through experimentation, trial and error.

In contrast, the systematic developers approached tasks by reading first:

In our test, we note that these [systematic] developers took some time to explore the API and to prepare the development environment before starting with the first task. Moreover, they took some time to get a general orientation. For example, P7 and P8 [persons 7 and 8] studied some sections in the documentation, then sent a GET request to the API and analyzed the response to check whether the request-response process worked as expected.

In short, systematic developers follow a “read-first, try-later” approach (while opportunistic developers follow a “try-first, read-later” approach). Pragmatic developers mix the two: “try-read / read-try.”

Although it might seem convenient to divide learning styles out by systematic, opportunistic, and pragmatic behaviors, researchers also found that the same developers did not always exercise the same behavior. Whether one approaches a task opportunistically versus systematically versus pragmatically might very well depend on the nature of the problem. For simple API requests, carefully reading the documentation probably isn’t warranted. But for complex API requests, where the developer might be totally stumped from the start, reading the documentation systematically might make sense.

The researchers explain that “the strategy a developer follows does not seem to predict a tendency towards using information from the Concepts page in our test.” In other words, just because you’re an opportunistic user, it doesn’t mean you always skip conceptual explanations — it’s just that you might not start with concepts. A non-linear reader might start with code, trying it out on their own, and circle back to the introductory conceptual information when the code doesn’t work as expected.

Deciding to cater to one type of behavior at the expense of the other might not be practical, since the learning behaviors and approaches seem to be in much greater flux than it seems.

When I’m writing docs and structuring my help system, I admit that I often have the more systematic developer in mind — the one that will read the material from start to end, the one who begins at step one, reads conceptual introductions, and then proceeds to the code examples and such. But that learning preference doesn’t describe a huge percentage of learners. It’s probably better to design for the opportunistic behavior, since this behavior pattern tends to go against our natural inclinations for linear and top-down information design. The linear/systematic behavior might be accommodated by default (since we tend to write linearly), while the non-linear/opportunistic behavior pattern is more likely to be neglected.

Designing for opportunistic behavior

How do you design for opportunistic behavior? If you recognize that users learn through experimentation and action, you’ll put more emphasis in code comments and code samples, error messages, troubleshooting, interactive experiences (such as Swagger UI) so developers can try out requests, clear navigation, and search to facilitate the user jumping around for specific information.

The authors call out some of these design patterns in their recommendations. The second half of the article provides recommendations such as:

- “Provide transparent navigation and a powerful search function”

- “Provide clean and working code samples”

- “Enable fast use of the API”

- “Provide important information redundantly”

- “Organize the content according to API functionality”

Note that “opportunistic” isn’t the author’s own terminology choice (it’s a term previous researchers used). The authors say that opportunistic behavior “bears many similarities with the exploratory and active approach described by John Carroll …”, referring to Carroll’s seminal work in The Nurnberg Funnel, which ties in with Mark Baker’s “Every Page Is Page One” and other nonlinear reading behaviors. Readers jump around, gathering information after exploring the system with trial and error.

Instead of “opportunistic” (which has a somewhat negative connotation), others have also characterized this behavior as “exploratory” or “active” or “bottom-up” learning. See How to design documentation for non-linear reading behavior and Principle 2: Make information discoverable as the user needs it for more information.

Where users spend the most time

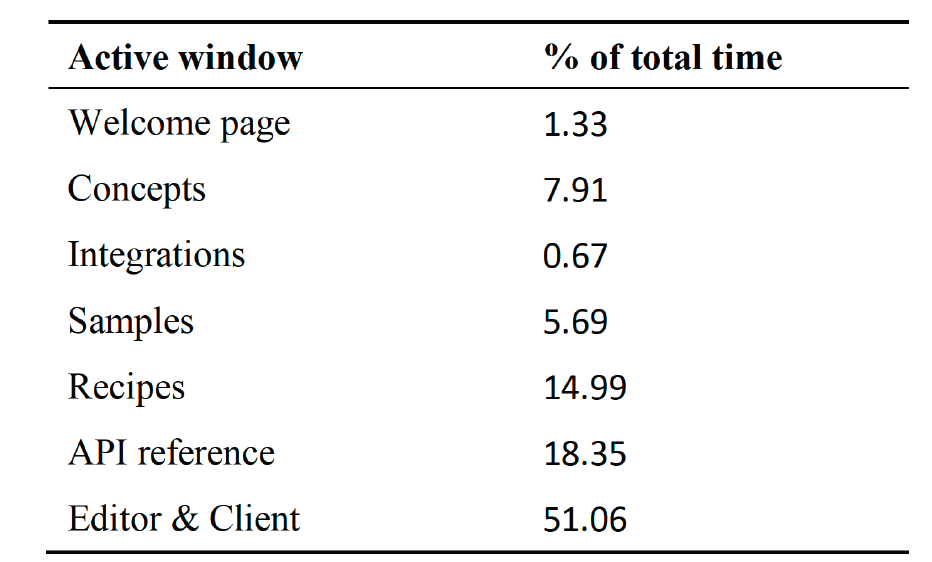

If developers jump around from code to concepts and other places, where are they spending most of their time in the docs? If we can measure the time in one type of documentation more than another, we can give more attention to that kind of documentation. The authors measured the time users spent in various parts of the documentation as follows:

Similar to the previous research from Head et al., ““When Not to Comment,” developers spent most of the time looking at API reference information (e.g., parameters). But here the researchers make an interesting observation that breaks other assumptions: they say developers looked for topics rather than categories of information — in other words, they didn’t necessarily distinguish between concepts versus recipes versus reference information types as they searched for information. They had a problem to solve, and they looked for information related to that problem, regardless of whether that information might be classified as a concept, task, reference, troubleshooting, recipe, or other topic type. As a result, the researchers recommend a more topic-based organization strategy:

Organize the content according to API functionality. A first aspect concerns the high-level organization of the API documentation. From the results of our study, we conclude that API documentation should be structured according to categories that reflect the functionality or content domain of the API rather than using categories that signal the type of information provided. Instead of dividing documentation into “Samples,” “Concepts,” “API reference” and “Recipes,” the API used in our study should be reorganized using categories such as “Shipment Handling,” “Address Handling” and so on. If developers experience a problem while working with the API and turn to the API documentation to find information that solves the problem, they are likely to know the content domain of their problem (such as shipments or address handling), but it is more difficult for them to predict whether the information they are looking for is presented in the API reference, in a section dedicated to presenting code examples, or in a section discussing concepts. Note that this guideline can be viewed as an application of the principle of minimalist documentation according to which the components of the documentation should reflect task structure (van der Meij & Carroll, 1995).

This is a somewhat radical recommendation because almost all API docs clearly separate out the reference information and label it as such. But perhaps the conceptual and recipe-based information can more easily integrate and re-use information from the reference section in seamless, unified ways. That way, if you’re looking for information on Shipping Handling (the example in their study), you might see the relevant Shipping Handling endpoints and parameters as well as Shipping Handling introductions and tutorials right in the same place (instead of jumping over to Reference for the Shipping Handling endpoint, then back to Recipes for how it might be used, and then over to Concepts for other Shipping Handling information).

It makes sense to have a Reference section where all endpoints are listed, but if this is the only place where these endpoints are described, this pattern might not be most convenient for users.

The authors also recommend that you integrate concepts with their related tasks:

Present conceptual information integrated with related tasks. Another aspect relevant in this respect concerns the integration of conceptual information that developers need in order to use the API successfully. Confirming results reported in Meng et al. (2018), our study supports the conclusion that developers vary with respect to whether they use conceptual overviews that introduce important API concepts in a systematic way. While some developers use such offerings, others tend to ignore them. To reach both groups of developers, conceptual information should not be aggregated in a dedicated section or document that signals to focus on conceptual information. We recommend presenting conceptual information integrated with the description of tasks or usage scenarios where knowledge of these concepts is needed. To give an example from the API used in our test, information regarding the representation of a shipment should be introduced in the section describing how to create a new shipment, and specific features of a return shipment should be provided in the section describing how return shipments are handled.

As much as tech writers might like to separate out information into different topic types (following patterns like Information Mapping or DITA), creating topics that clearly separate out concept from task from reference and troubleshooting topics constitutes a big fail in terms of usability, since developers need all of this information as they explore the problems they attempt to solve. If you are separating out this information, hopefully you’ve structured your help system in a way such that the information is closely linked or integrated with each other.

Conclusion

While the learning styles discussed in this article might seem more applicable to overall documentation (rather than our specific focus on code documentation), the takeaway with code documentation is pretty clear: when you document code, the code should be easy to experiment with. Can users copy and paste it into their own IDEs and make it run? Can they copy and paste requests into Postman and get immediate responses that they can learn from?

More than any other type of API documentation, when you document code you find yourself with a direct opportunity to target the opportunistic learning style with experiment-and-try opportunities.

Takeaways from the Research

To summarize the takeaways from the research presented here, here are some key points:

- Omit documentation when the code is simple and understandable on its own.

- Write code documentation while the project is fresh and active in developer’s minds.

- Make sure the reference documentation (e.g., parameters) is complete and accurate, since this documentation is where developers spend most of their time.

- Include documentation both in regularly expected locations as well as peppered in the code itself with inline comments.

- To accommodate non-linear, opportunistic behaviors, design your help system with healthy doses of code, interactive API explorers, search features, troubleshooting information, and cross-references.

- Organize information by the function it provides rather than by its information type (task, concept, reference, etc.).

- Make code easy to experiment with so that people can learn directly through these experiences.

These strategies provide a foundation for best practices that we will explore in more detail with more concrete, tangible techniques in the sections that follows.

84/145 pages complete. Only 61 more pages to go.