Code samples

Developer documentation tends to include a lot of code samples. These code samples might not be included with the endpoints you document, but as you create tasks and more sophisticated workflows about how to use the API to accomplish a variety of goals, you’ll end up leveraging different endpoints and showing how to address different scenarios. Code tutorials are a crucial part of your user guide.

- Code samples are like candy for developers

- Don’t just provide reference docs

- Focus on the why, not the what

- Add both code comments and before-and-after explanations

- Keep code samples simple

- Make code samples copy-and-paste friendly

- Provide a sample in your target language

- Sample code tutorials

- Code samples for sample weather API

- Activity with code samples

Code samples are like candy for developers

Code samples play an essential role in helping developers use an API. Code is literally another language, and when users who speak that language see it, the code communicates with them in powerful ways that non-code text (however descriptive it is) can’t achieve.

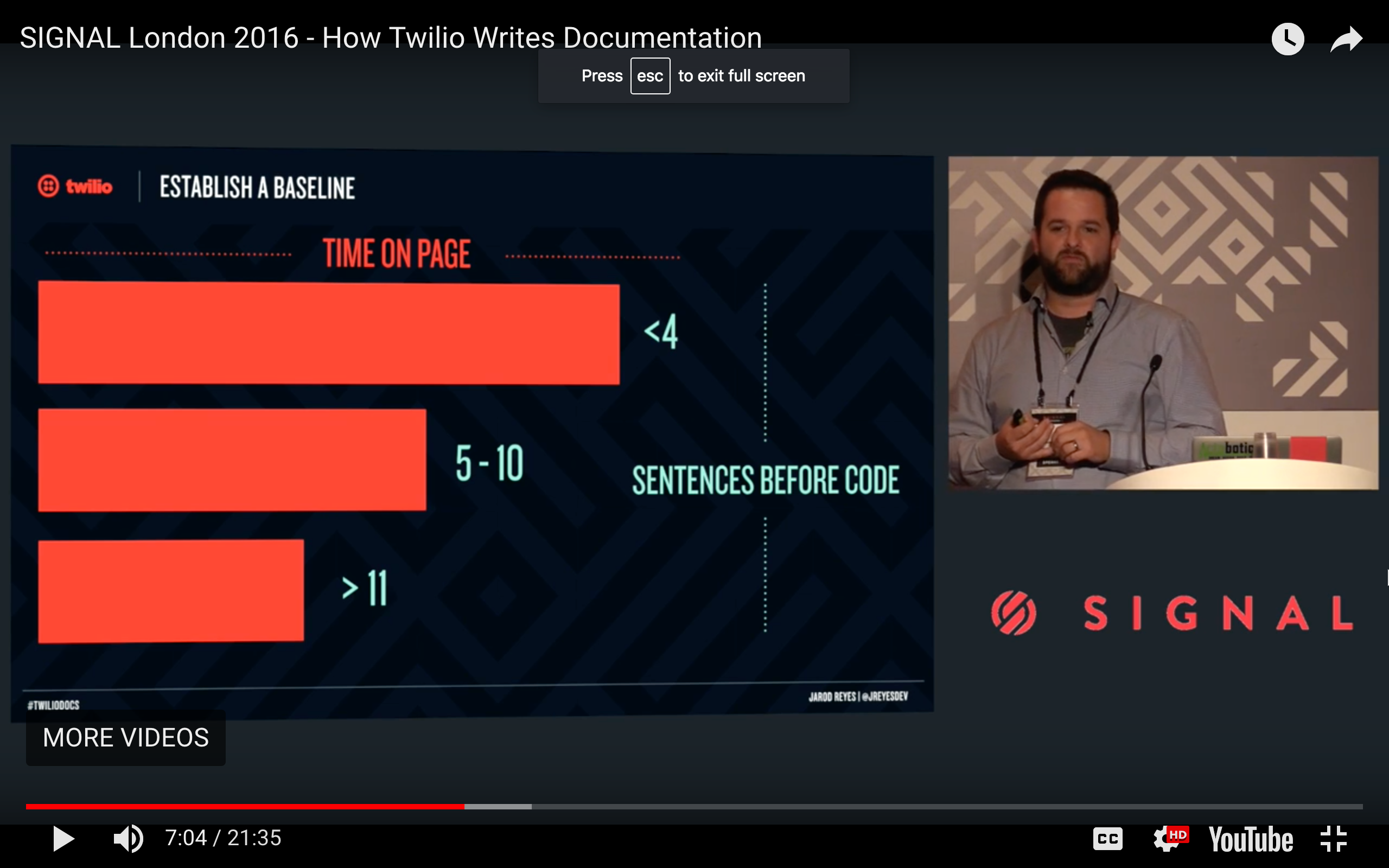

In user testing that Twilio did with their documentation, they found that pages that started more quickly with code samples performed better with users.

Specifically, pages with less than 4 sentences before code samples performed twice as well as pages with 11 sentences before code samples. Jarod Reyes explains:

It’s a mental block more than it is not being able to see code. It tells a developer that this page has a lot to say, and that they have a lot to do. They don’t want to necessarily want to spend the time to read what you want to say. We saw this across section length; we saw this across page depth. Any time that there is a lot of prose on a page and not a lot of code, that page didn’t perform well. (How Twilio Writes Documentation)

In other words, when developers see code, it’s the equivalent of seeing a task-based topic with a user guide — the code indicates a concrete action for the developer to take. This attracts the developer’s attention.

Don’t just provide reference docs

Sometimes engineers want to avoid including code samples in API docs because they feel the endpoint reference documentation contains all the information developers need and stands on its own. However, this view is often shortsighted. In an article on the Programmable Web called The Six Pillars of Complete Developer Documentation, the authors explain:

While a developer’s guide should walk a developer through the basic usage of an API and its functionality, it can’t cover every possible use of that API in a coherent way. That is where articles and tutorials come in, to teach developers tangential or specialized uses of an API, like combining it with another service, framework, or API.

In other words, the articles and tutorials complement the reference documentation to provide complete instruction. Code samples that show how to use the various endpoints to achieve a goal occupy an important space in your user guide.

Additionally, even if including code samples, the level of detail and explanation is also somewhat debatable. Many developers assume that the developer audience has a skill set similar to their own, without recognizing different developer specializations. And so they will add a code sample but not give any explanation about it. Internal developers will often say, “If the user doesn’t understand this code, he or she shouldn’t be using our API.”

If you encounter this attitude, remind developers that users often have technical talent in different areas. For example, a user might be an expert in Java but only mildly familiar with JavaScript. Someone who is a database programmer will have a different skill set than someone who is a Python programmer, who will have a different skill set from a front-end web development engineer, and so on. Given these differences and the likely possibility that you will have many novice (or unfamiliar) users, more extensive code tutorials and explanations are warranted.

Focus on the why, not the what

Once you have code samples in your documentation, the next question is how to document them. User interfaces have clear tasks — buttons to click, linear workflows, etc. But documenting code can be more of a conundrum. Remember this basic principle: In any code sample, focus your explanation on the why, not the what. Explain why you’re doing what you’re doing, not the detailed play-by-play of what’s going on, especially when the what refers more to standard programming mechanics that aren’t unique to your API.

Here’s an example of the difference:

- what: “In this code, several arguments are passed to jQuery’s

ajaxmethod. The response is assigned to the data argument of the callback function, which in this case issuccess.” - why: “Use the

ajaxmethod from jQuery because it allows for asynchronous responses that won’t block the loading of your page.

Developers unfamiliar with common code not related to your company (for example, the .ajax() method from jQuery) should consult outside sources for tutorials about that code. Don’t write your own version of documentation for another programming language or service. Instead, focus on the parts of the code unique to your company. Let the developer rely on other sources for the rest (feel free to link to other sites).

Add both code comments and before-and-after explanations

Your documentation regarding the code should mix code comments with some explanation either before or after the code sample. Different languages have different conventions for comments, but generally brief code comments are set off with forward slashes // in the code; longer comments are set off between slashes and asterisks, like this: /* .... */.

Comments within the code are usually short one-line notes that appear after every 5-10 lines of code. You can follow up this code with more robust explanations in your documentation, but it’s ideal to pepper code samples with comments because it puts the explanation next to the code doing the action. This approach of adding brief comments within the code, followed by more robust explanations after the code, aligns with principles of progressive information disclosure that help align with both advanced and novice user types. In this case, progressive information disclosure means you provide some detail in the context of an activity, and then add links or references for more information if the user needs it.

If you have comments interspersed in code as well as in conceptual sections before or after the code, won’t that be somewhat redundant? Not really. Some research about how developers use documentation found that there are two common behaviors: developers who start in code and read higher-level conceptual documentation only as needed (called “opportunistic” behavior). And developers who start in higher-level conceptual documentation before working their way down to code (called “systematic” behavior). Michael Meng, Stephanie Steinhardt, and Andreas Schubert explain:

Once a high-level understanding of the API purpose and features has been formed, two different pathways seem to emerge that closely resemble the “systematic” and the “opportunistic” developer personas described by Clarke (2007) (see also Stylos, 2009). According to Clarke (2007), developers represented by the systematic developer persona work top down in the sense that they try to get a deeper understanding of the system as a whole before turning to individual components. On the other hand, the learning goals of opportunistic developers are more narrowly focussed on solving a particular problem and dependent on the specific issues and blockers they encounter while working toward a solution (“Application Programming Interface Documentation: What Do Software Developers Want?” Journal of Technical Writing and Communication. 2018, Vol. 48(3) 295–330. ResearchGate)

For the opportunistic developer that first starts in the code, comments in the code can provide helpful documentation to get the developer oriented quickly. But not everyone starts in the code. Some prefer to read the conceptual overviews first.

For more research on how to document code, see “When Not to Comment: Questions and Tradeoffs with API Documentation for C++ Projects” by Andrew Head, Caitlin Sadowski, Emerson Murphy-Hill, and Andrea Knight (2018 ACM/IEEE 40th International Conference on Software Engineering. ResearchGate). The researchers explore whether developers are more apt to look in header files (where more formal descriptions of the class and methods appear) or implementation code for documentation (they focused on C++). In some cases, reading the implementation code directly provides a clearer path to understanding for developers. Additionally, some developers distrust that documentation is up to date and so prefer to look at the code directly. For more complex code, however, learning from more elaborate documentation in header files was helpful.

Overall, not every programmer reads code the same way. But based on the research, it’s a good idea to include comments directly in the code as well as more formal explanations outside the code. If developers give you a chunk of code that has comments peppered throughout, don’t assume that the code comments are somehow separate from documentation or outside your stewardship as a technical writer. Think of comments in code as the equivalent of context-sensitive help in a user interface — in many ways, this might be the most read content of all.

Keep code samples simple

Code samples should usually be stripped down to their simplest possible form. Providing code for an entire HTML page is probably unnecessary. But including some surrounding code doesn’t hurt anyone, and for newbies, it can help them see the big picture. (It’s also easier to copy and paste.)

Additionally, avoid including a lot of styling or other details in the code that will potentially distract the audience from the main point. The more minimalist the code sample, the better. For example, if you’re showing a simple JavaScript function, you might be tempted to support it with elaborate CSS styling so that the demo looks sharp. However, all the extra CSS will only introduce more complexity and confusion that competes with the original principle you’re trying to show with the code sample.

When developers take the code and integrate it into a production environment, they’ll probably make a lot of changes to account for scaling, threading, and efficiency, and other production-level factors. But don’t start out this way just to have a polished and professional looking demo.

Make code samples copy-and-paste friendly

Many times developers will copy and paste code directly from the documentation into their application. Then they will usually tweak it a little bit for their specific parameters or methods.

If you intend for users to copy and paste the code, make sure it works. When I first used some sample ajax code from a code tutorial on an API site, the dataType parameter was spelled datatype. As a result, the code didn’t work (it returned the response as text, not JSON). It took me about 30 minutes of troubleshooting before I consulted the ajax method and realized that it should be dataType with a capital T.

Ideally, test out all the code samples yourself (or implement a more robust process for testing code). Testing allows you to spot errors, understand whether all the parameters are complete and valid, and more. In the earlier video from Twilio, the authors say they wanted to treat code samples in documentation like their other engineering code, so they stored their code in a separate container (also pushed to GitHub) to run regular tests on the code. They pulled the code into their documentation where appropriate. For lengthy code samples, consider storing the code on GitHub. This way engineers can more easily test it as part of their test cases for each release. Sometimes when code blocks are buried in documentation, they’re overlooked with new releases.

Provide a sample in your target language

With REST APIs, developers can use pretty much any programming language to make the request. One question will inevitably arise: Should you show code samples that span across several languages? If so, how many languages?

Providing code samples is almost always a good thing, so if you have the bandwidth to show code samples in various languages, go for it. However, providing just one code example in your audience’s target language is probably enough. If there isn’t a standard language for most users, you could also just provide the curl examples in your docs, and then provide users with a Postman collection or an OpenAPI specification file — both of these approaches will allow developers to generate code samples in many different languages.

Remember that each code sample you provide needs to be tested and maintained. When you make updates to your API, you’ll need to update each of the code samples across all the different languages. When your API pushes out a new release, you’ll need to check all the code samples to make sure the code doesn’t break with the changes in the new release (this is called “regression testing” in QA lingo).

Including a lot of code samples increases the amount of testing and maintenance, but this is the most helpful type of content for users. Take an approach that you can support and maintain.

Sample code tutorials

The following are a few samples of code tutorials in API documentation.

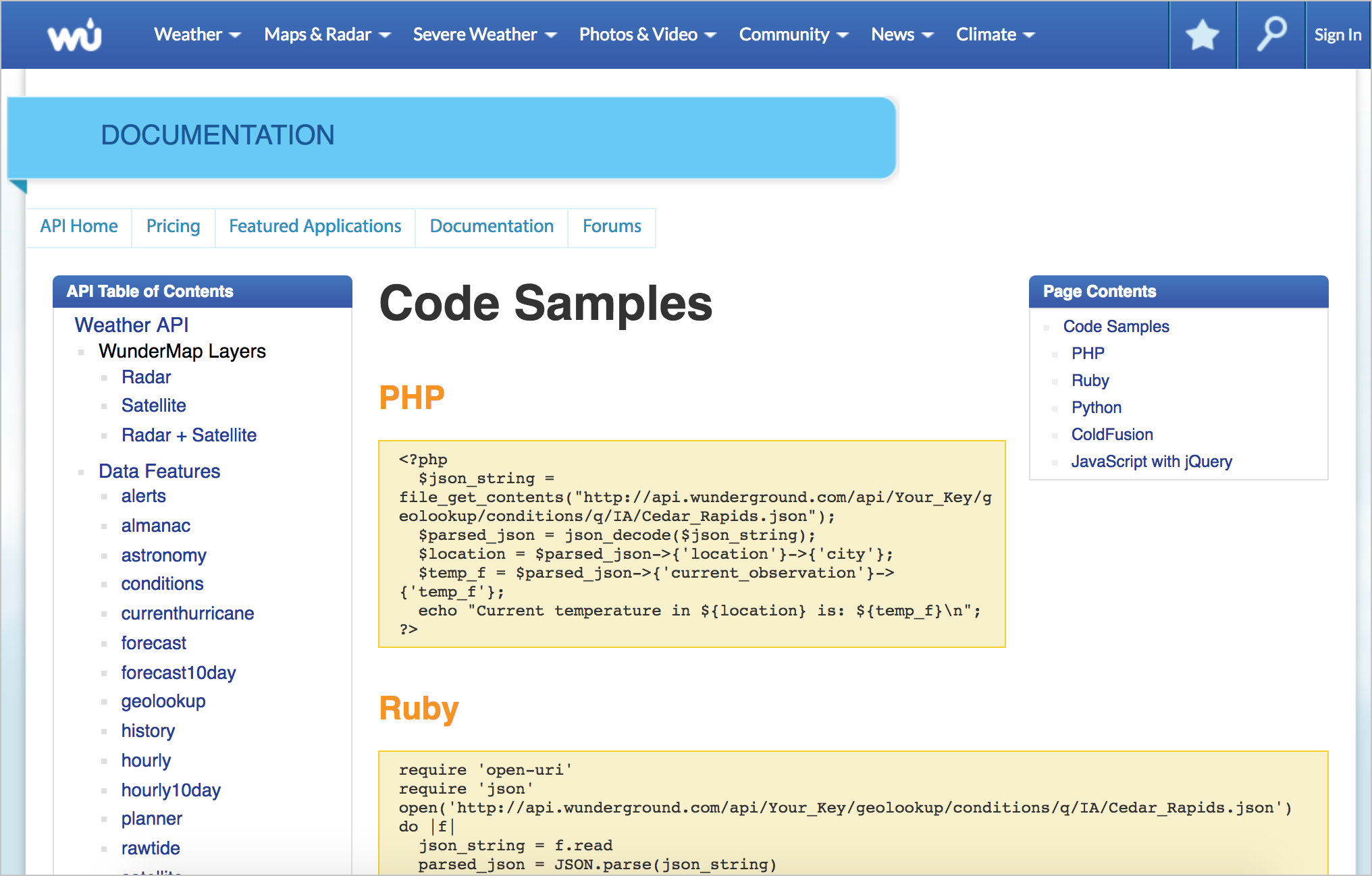

Weather Underground

In this Weather Underground example, there are various code samples across half a dozen languages, but no explanation about what the code sample returns. In this case, the code is probably simple enough that developers can look at it and understand from the code itself what’s going on. Still, some explanation is usually warranted, especially if there are multiple ways to make the call.

Sometimes developers will tell you that code is “self-documenting,” meaning it’s evident from the code itself what’s going on. Without a knowledge of the programming language, it’s hard to evaluate this statement. If you encounter this question, consider checking this assertion with some other engineers, especially outside the product team (or with users, if you have access to them).

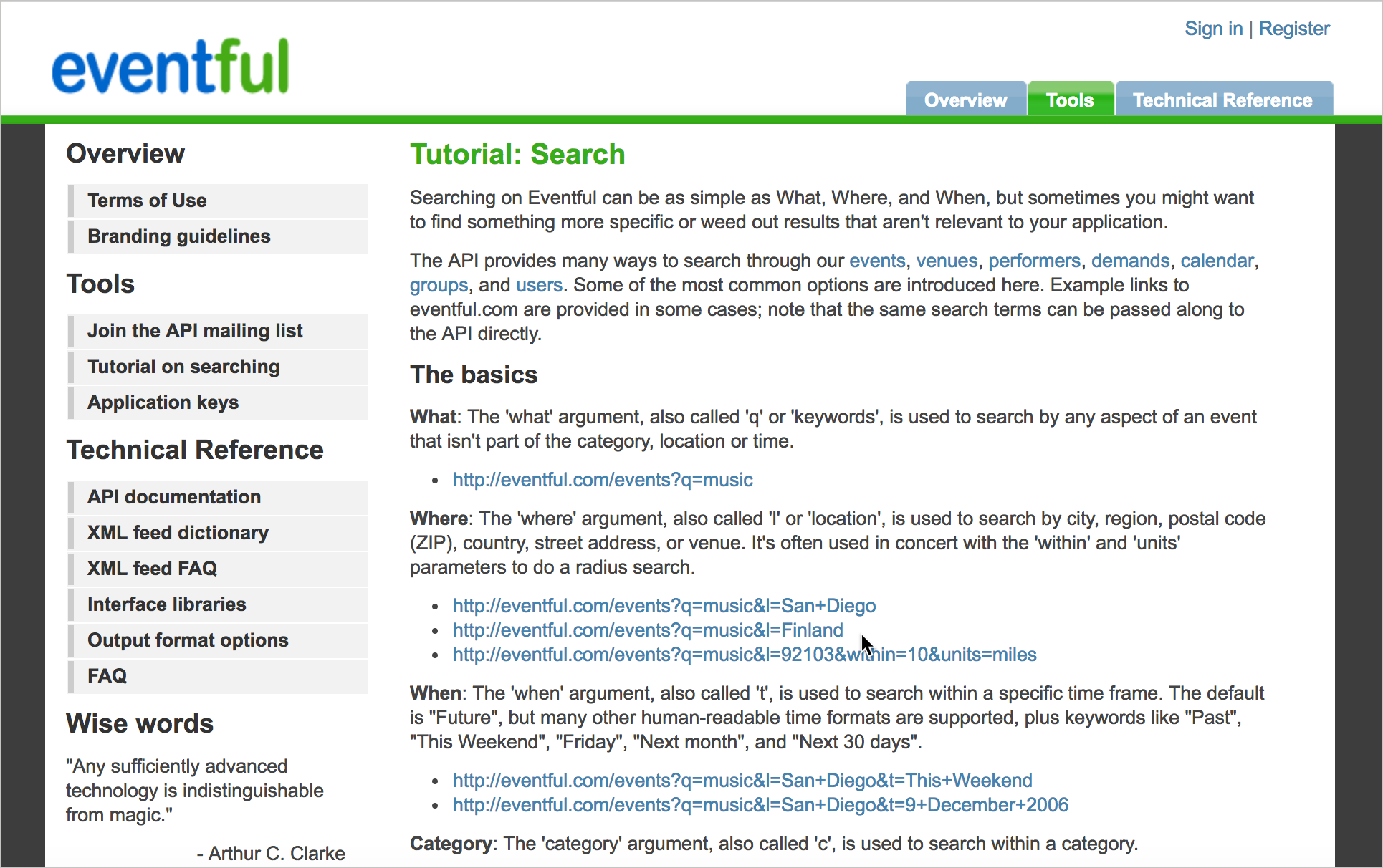

Eventful

You won’t see chunks of code here, but the Eventful docs include various examples about query string parameters for the endpoints. Although these parameters are also defined in their reference documentation for the search endpoint, the tutorial here expands on how to use the parameters in a more friendly, detailed way.

I like the Eventful tutorial because it shows how documentation that is usually contained in reference material can be pulled out and explained more narratively with examples. It shows more of the difference between reference and tutorial information.

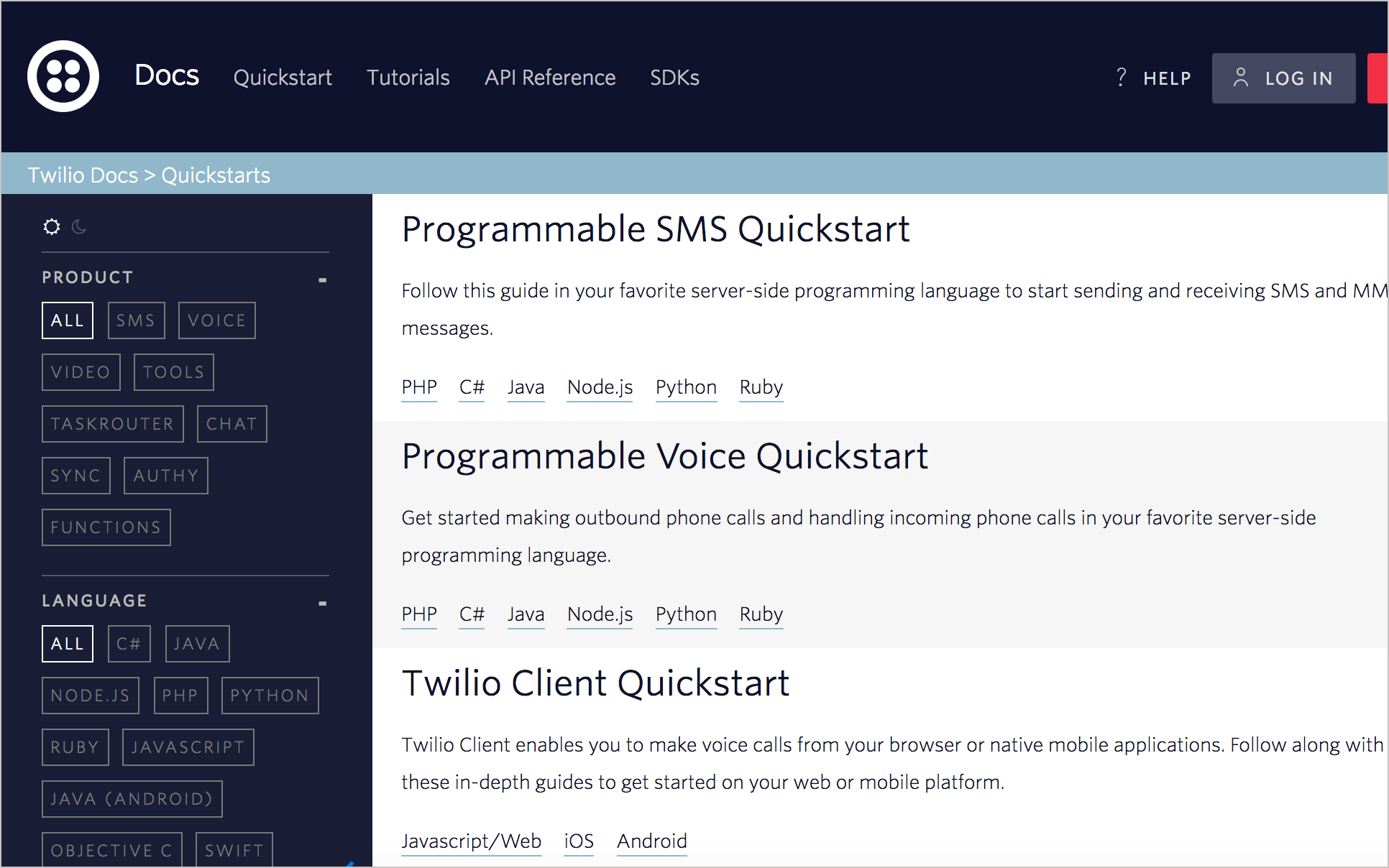

Twilio

Twilio’s tutorials are probably the most impressive and fully detailed tutorials in the examples here. Not only do they walk users through a task from beginning to end, they do so in half a dozen languages. The specific code examples have been extracted out into the right-column, while the narrative of the tutorial occupies in the middle column. All the steps in the tutorial aren’t shown at once. When you reach the end of one step, you click a button to show the next step. This progressive disclosure of information might reduce any sense of intimidation users might feel when beginning the tutorial.

Although the middle column is narrow and the right-column larger, actually this middle column just contains narrative text to annotate and explain the code. When you click a button in the tutorial, it brings the code on the right in focus and blurs the other code. Their implementation is a technical feat that I haven’t seen anywhere else.

Mailchimp

As usual, Mailchimp provides solid tutorials for their products. The “Before You Start” section lists any necessary prerequisites before starting the tutorial. Each part of the tutorial is set off with section headings.

The section heading style (rather than numbered steps) is worth considering. Most technical writers have numbered steps as a habit for tech docs, so when they start writing a code tutorial, the first inclination is to begin a sequence of steps. But with a code tutorial, you might have lengthy code samples that are followed by detailed explanations, and so on. Maintaining the list numbers across steps can become onerous. The section headings provide less problematic formatting, and you can still preface each section heading with “Step 1”, “Step 2”, and so on.

IBM Watson

The IBM Watson tutorial does an excellent job breaking up the tutorial steps into different sections, with easy-to-follow steps in each section. Up front, it lists the learning objectives, duration, and prerequisites. There’s nothing particularly challenging about the formatting or the display — the emphasis focuses on the content.

Code samples for sample weather API

Earlier in the course, we walked through each element of reference documentation for a fictitious new endpoint called surfreport in the weather API we were working with. Let’s return briefly to that scenario and assume that we also want to add a code tutorial for showing the surfreport on a web page. What might that tutorial look like? Here’s an example:

Code tutorial for surfreport endpoint

The following code samples show how to use the surfreport endpoint to get the surf height for a specific beach.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<head>

<script src="https://code.jquery.com/jquery-2.1.1.min.js"></script>

<script>

// limit the result through days parameter to keep the returned data set light

var settings = {

"async": true,

"crossDomain": true,

"url": "https://api.openweathermap.org/surfreport/25&days=1",

"method": "GET"

}

// use ajax method to allow for asynchronous calls that won't block page loading

$.ajax(settings).done(function (response) {

console.log(response);

$("#surfheight").append(response.surfreport.conditions);

});

</script>

</head>

<body>

<h2>Surf Height</h2>

<div id="surfheight"></div>

</body>

</html>In this example, the ajax method from jQuery is used because it allows us to load a remote resource asynchronously.

In the request, you submit the authorization through a query string URL. The endpoint limits the days returned to 1 to increase the download speed.

For demonstration purposes, the response is assigned to the response argument of the done method, and then written out to the surfheight tag on the page.

We're just getting the surf height, but there's a lot of other data you could choose to display.

One could go into a lot more detail with the explanation, even going line by line through the code, but here the commentary is already about half the length of the code. And there are some comments interspersed in the code. The comments address more the question of “why” rather than “what.”

Documenting code can be one of the most challenging aspects of developer documentation. Part of the challenge is that code isn’t organized such that a line-by-line (or block-by-block) description makes sense. Variables are often defined first, functions are called that are defined elsewhere, and other aspects are non-linear as well. As you explain the logic, you might find that you’re jumping around to different places in the code, not necessarily moving from top to bottom.

For a deeper dive into how to document code samples, see my presentation on Creating code samples for API/SDK documentation.

Activity with code samples

With the open-source project you identified, identify code samples in the API documentation. Answer the following questions:

- Are there code samples provided? In which languages?

- How many code samples are there? Lots? Just a few? None?

- Are there comments within the blocks of code?

- How do the conceptual explanations point to specific lines of code? Is the explanation given before, during, or after the blocks of code?

- Do the code explanations focus more on the “why” (the decisions behind the code) or the “what” (the mechanics of the code)?

86/145 pages complete. Only 59 more pages to go.